Of all the classic radios, record players and music boxes displayed in our beloved museum, nothing seems to delight folks quite like the sight and sound of our 1936, WURLITZER Simplex Multi-Selector coin-operated phonograph—more commonly known as, a jukebox.

This mechanical marvel invites guests to smile, sway, even swing to the sounds of Tony Bennett, Frankie Lane, and other classic music makers from Radio’s Golden Age. We’ve seen grown men cry like little girls as Nat “King” Cole conjures-up a familiar melody—like it was yesterday!—remembering a time when love was new and exciting. Children become transfixed as they gaze through the glass window, watching the platter spin as the record floats in mid-air.

Absolutely magical.

The story of how the world’s most popular music machine came into existence begins with America’s most famous and influential inventor.

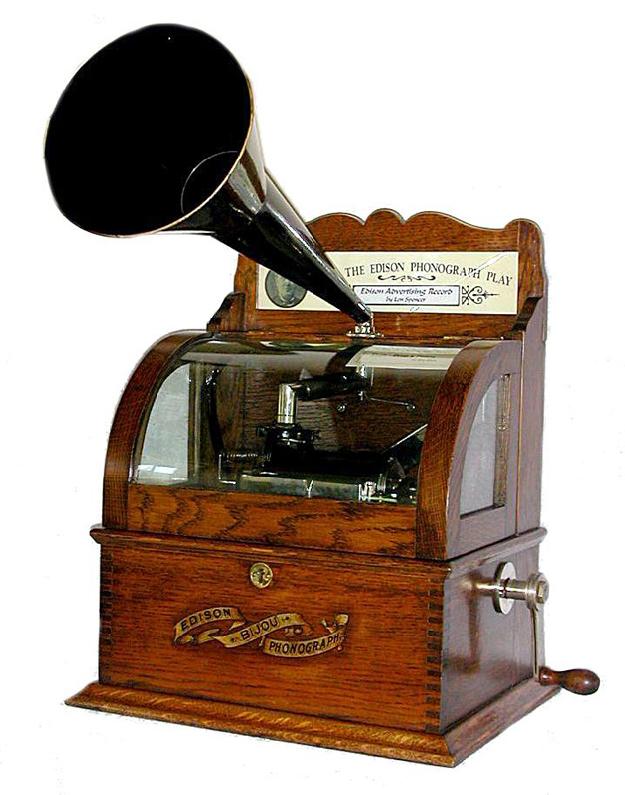

Thomas Alva Edison, before going on introduce the lightbulb, and the motion picture camera, sold the rights to manufacture his tinfoil phonograph—one of the world’s first—insisting it be used as a business machine, while barely tolerating its exploitation as a medium of entertainment.

But Edison miscalculated the desires of the American public; it was, in fact, an Edison machine that was first fitted with a coin slot by Louis Glass, and installed at the Parlays Royale Saloon in San Francisco, California on November 23, 1889, as the first official coin-operated phonograph.

Individuals were treated to two minutes of music by pressing an ear against one of the four listening tubes. These first music machines never had the cultural impact their descendants enjoyed, simply because they could only be heard by a few people at a time. Nonetheless, as an amusement, its novelty so sparked the curiosity of the public that it quickly became the basis for a thriving industry.

Rudolph Wurlitzer, a German immigrant who previously manufactured oompha organs for merry-go-rounds (and would go on to produce The Mighty Wurlitzer theatre organ), decided there was a future in producing these curious music machines and, along with his three sons, introduced the first of what would soon be known as The Wurlitzer Automatic Phonograph.

These first automated music devices played 78 rpm records, and remained little more than a coin-operated novelty, like gumball machines and penny arcades, until 1927 when several companies—including Wurlitzer—introduced electrically amplified instruments.

“Electrical amplification was the game-changer that made these early machines so popular,” says John Jenkins, Museum president and co-founder. “Suddenly, businesses didn’t need an orchestra to entertain large groups in big spaces, you just needed a nickel.”

Even during the Great Depression, people could still afford five cents to hear “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” on the local jukebox. Prohibition didn’t hurt either, since every speakeasy had to have music, but few could afford a live band. By 1932, there were over 250,000 coin-operated phonographs spinning popular music throughout the country.

Model 312 from the SPARK Museum’s collection

It was about this time the term “jukebox” became synonymous with what was previously known as the “automatic phonograph.” Some suggest the term originated from “jook”, an old southern word of African origin meaning to dance. Still others feel the term had a more overt sexual connotation, like “boogie”, and a juke joint was actually a house of ill repute. Either way, by the 1930s jukeboxes had replaced the player piano, keeping patrons dancing upstairs, and down.

Another popular term often associated with coin operated record players is “nickelodeon,” which originally referred to the five cent cinema and movie houses in Europe. In the United States, the term has come to include any early coin-operated piano, music box, or record player.

In 1936, Wurlitzer hired legendary design engineer, Paul Fuller, (1897–1951), who would go on to become as fundamental to the success of the coin-operated phonograph as anything in the mechanism, the speaker, or the marketing—even as important as the magical floating turntable.

That same year, The Wurlitzer Company would launch a series of coin-operated phonographs, and go on to create the most popular and recognizable jukeboxes in music history.

In the early 1930s automatic phonograph cabinets were sedate and looked more like traditional furniture. Fuller wanted his record playing machines to be bright and inviting, and was influenced by art deco’s extreme lines and rounded form.

“It was Fuller who later introduced illuminated plastics into the cabinetry,” says Charlie Bryan, Visitor Engagement Manager. “It’s like Christmas every time you play a song.”

Fuller’s first Wurlitzer Music Machine, The Model 312, Simplex, Multi-Selector Phonograph is the first coin-operated phonograph designed by Paul Fuller for Wurlitzer, and the first in their new line of music machines.

Standing at approximately 60 inches, The Wurlitzer, Model 312 is, at first glance, strikingly beautiful: The cabinet is meticulously crafted in a rich mixture of mahogany and contrasting veneer. The gold mesh “jailhouse” grill covers a powerful 15 inch loud speaker, capable of filling any dance hall or nightclub with the popular music of the day.

The large glass window allows patrons to see the mechanism in full-swing, with “Wurlitzer” stenciled across the top. There are twelve artist title strips, backlit in glowing orange for easy song identification.

On the center right of the cabinet is an illuminated dial with twelve selections, and features bright white and red plastic buttons.

Step One: Press the center red button

Step Two: Select any of the twelve options

Step Three: Slide a nickel in the coin-slot,

and let the show begin!

As soon as your coin drops—and Mr. Wurlitzer gets his nickel—the machine jumps into life! Suddenly, the window is filled with bright electric light, reveling all the crazy mechanical action about to take place inside.

In the blink of an eye, your song selection is snatched from the stack of twelve record rings on the left, and slides the selected song into the center of the frame. Then—out of nowhere—a felt covered platter rises-up, and suspends the disk in mid-air, as the “bear claw” tonearm drops into view, and the needle catches the groove on the spinning disk.

Voilà, out comes music!

Well, almost.

“These early jukeboxes have a minor flaw in that the tubes have to warm-up before any sound comes out,” says Jenkins. “When you begin from a cold start, you miss the first few seconds of the record because the vacuum tubes need a little time to warm-up.”

Not a common problem with today’s computerized recordings.

Yet, we feel nothing beats hearing an original 78 rpm record on a machine in which it was born to be played. Next time you visit, be sure to swing through our Golden Age of Radio gallery, and ask for a demonstration.

We’ll even let you pick the song.

Stay grounded:)