Not very long ago, if you wanted to purchase your favorite song, you couldn’t just go to iTunes or Amazon Music (they didn’t exist), and your favorite song wouldn’t instantly appear on your cell phone or computer (they didn’t exist, either).

If you went to a store to buy your favorite song, it would not come in a sleeve or dust jacket, and it would not be made of vinyl or tape. Your favorite song—if you could find it—would not be digital or analog or even require electricity.

If you wanted to hear your favorite song, and were too lazy or tone-deaf to master a musical instrument, or too cheap to hire a professional musician, you only had one option.

The music box is a mechanical device that produces a variety of tones using a set of metal prongs, which are tuned and plucked with tiny pins on a revolving cylinder or disc. Every pin represents a tone, and that pattern of pins are organized to make a delicate, enchanting melody.

Perhaps even your favorite melody, a song you can reproduce over and over again. No professional musician required. Just wind it up, and out flows your favorite song. Delightful, a little spooky, and always wonderous, the music box makes pretty, mechanical sounding music.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, another music reproducing machine captured the world’s attention. It also used patterns to create melodies, and required no electricity. Yet, unlike the music box, this machine reproduced more complex and intricate musical arrangements with an unmistakable human touch.

The player piano, or “pianola,” is a type of mechanical piano that can play music stored on a roll of paper. It operates using a system of perforated (holes) rolls, and a pneumatic (air) pedal system.

The pianola has a set of foot pedals connected to a series of pneumatic devices and vacuum systems. The foot pedals activate the pneumatic system, using air pressure to read the holes in the music roll, creating a self-playing piano that mimics the sound and movement of a pianist playing the piano.

The piano roll is the heart of the pianola, and uses a tone pattern much like a music box. A mechanism captures the pianist’s keystrokes and pedal movements onto a paper roll using a special machine that punches holes in the paper according to the timing and intensity of each note played. The placement and size of the punched holes on the paper roll represent different musical elements. For instance, the position of a hole determines the pitch of the note, and the size of the hole may indicate the duration and volume of the note.

This form of encoded music is highly detailed, resulting in a remarkably accurate reproduction of the pianist’s performance, without the pianist. Piano rolls were popular in the early 20th century, and allowed musicians to share their work with a broader audience—and more importantly, preserved these performances for future generations.

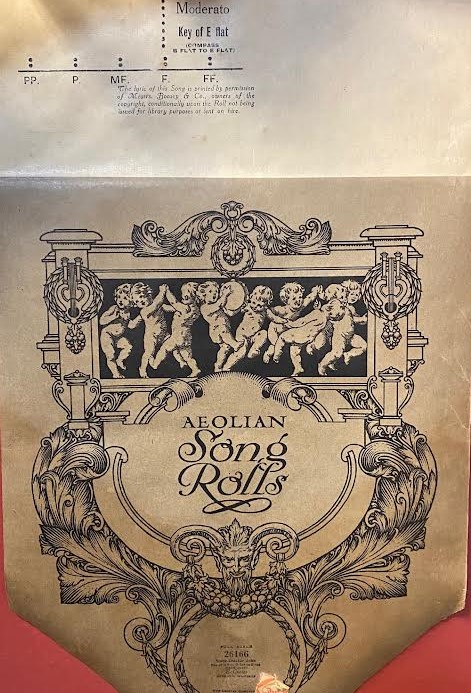

The artistry of the piano roll extended beyond the music itself and into the design of the rolls. Many were adorned with intricate and colorful illustrations, attempting to capture the essence of the music they contained. These designs ranged from elegant and artistic for classical compositions, to vibrant and exuberant for ragtime and show tunes.

The Roaring Twenties witnessed the zenith of the player piano craze. Jazz, ragtime, and the Charleston all found a home in the hearts of the public through pianolas. They were the stars of countless saloons, speakeasies, and grand parlors all across the country. People marveled at the incredible performances these instruments could deliver. The sensation of a piano playing itself was nothing short of magical.

As the pianola and its rolls evolved, the artistry and craft behind them continued to flourish, until it did not.

By the mid-20th century newer forms of entertainment and recorded music entered the scene with commercial radio and Edison record players leading the way. Soon everyone had a radio, TV or record player, and piano sales fell off the map, along with the pianola. Enthusiasts and collectors continue to preserve and restore these remarkable instruments, keeping the art of the pianola alive.

“This piano built upon approved scientific principles which guaranties perfect tone and the utmost durability.”

In the 1920s, The Franklin Piano Company produced a line of very well-made reproducing player pianos which were often elaborate and relatively expensive. A fine example of this mechanical marvel is on permanent display and demonstrated daily in the Museum’s interact galleries. Next time you’re visiting be sure and ask for a demo—then be prepared to experience a music machine with more moving parts than a Swiss watch, while recreating an amazingly human sound that is anything but mechanical. In the meantime, check out our SPARK SciShort on the Player Piano.

Stay grounded.