Nothing says Christmas like a pyramid shaped evergreen tree, tapered to a point, topped with a star, and filled with tiny lights that flash like stars embedded in the night sky.

The tradition of using lights to celebrate cultural and religious holidays can be traced back thousands of years to a variety of ancient civilizations, well before the time of Thomas Alva Edison and his famously illuminating invention.

Our story begins around 16th century Germany, where the use of candles for highlighting Christmas trees and holiday decorations first became popular. It is believed that Martin Luther (1483- 1546), the Protestant reformer, was one of the first to use candles on a Christmas tree. Luther felt the flickering flames would recreate the beauty of stars shining through the winter night. (All too often those same flames would recreate an apocalyptic towering inferno right out of the Book of Revelation.) Candles were attached to tree branches with wax or pins, which seems terribly dangerous—and it was.

Accidental holiday fires happened all the time, and everywhere. Homes, churches, hospitals—everyone with a Christmas tree took the chance of having their favorite holiday go up in smoke.

And yet, the practice of candle-lit Christmas trees continued to spread across Europe and the United States like, well, like wildfire.

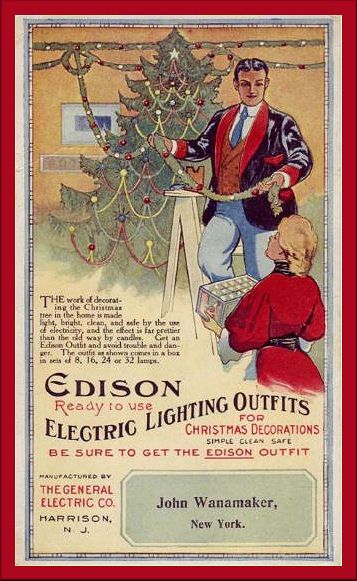

In 1882, just two years after Edison patented the first incandescent lightbulb, his assistant, Edward H. Johnson, hung the first known electric Christmas lights on a Christmas tree in New York City. Johnson, an inventor and electric light pioneer, hand-wired 80 red, white, and blue light bulbs and wrapped them around his Christmas tree. Everybody thought they looked fantastic, and thus marked the dawn of electric holiday lighting for the American home.

However, before the 1920s, most people didn’t have access to electricity, and early electric lights were expensive and not widely available, making candles the continued norm for most American households for several decades to come.

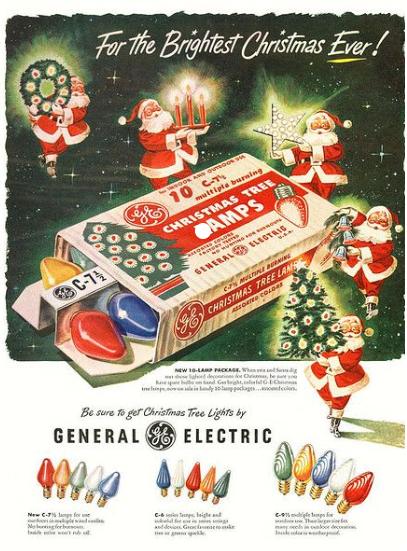

In 1919, General Electric launched their line of decorative, miniature string lamp Christmas kits. These kits were less expensive and featured a flame-shaped bulb using a longer lasting tungsten filament. The lights looked beautiful, and were a hit with the public—but finding a way to connect to existing sockets was a problem. Powering early electrical appliances like toasters, irons, and Christmas lights had to be connected to an existing light socket or fixture, usually located on the ceiling, making the link awkward and potentially dangerous.

Early electrical Christmas tree lighting—though a great improvement over open flames—still posed several safety issues, some of which were related to the technology of the time and others were due to unsafe practices. Just some of the obvious safety concerns associated with early electric Christmas tree lighting include —

Fire! Incandescent bulbs become very hot, creating an obvious fire hazard, especially when draped around flammable materials like dry evergreen branches on a dead tree.

Overload! Many early electrical systems were not designed to handle the additional load of holiday lights. People often connected multiple strands of lights to a single electrical outlet or circuit, which often led to overloading and overheating of the wiring, causing countless fires.

Live Wire! The insulation used on the wiring for early holiday lights seems frightening by today’s standards. Damaged or frayed insulation was the norm, often exposing live wires, and increasing the risk of electrical shock or short circuits.

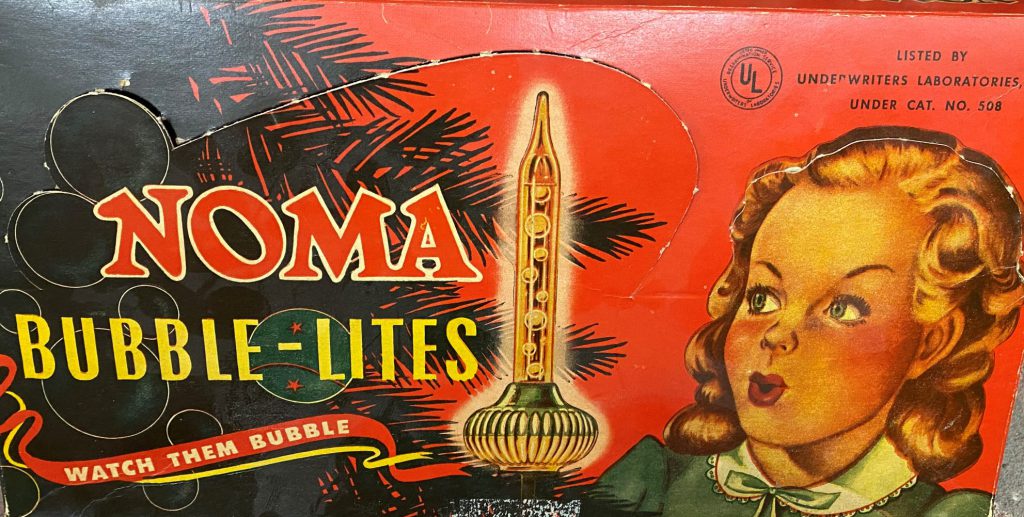

In 1927, inventor and industry pioneer, Albert Sadacca, started the National Outfit Manufacturer’s Association Electric Company (NOMA), and for the next 40 years became the largest Christmas light manufacturing organization in the world. NOMA would go on to make many significant improvements and innovations in holiday lighting, sometimes with mixed results.

Launched in the United States in 1946, the Noma Bubble Lit Christmas tree lights, got its name —not from the shape of the colorful bulb—but from their ability to create tiny bubbles, floating inside a little bulb filled with methylene chloride and heated just enough to where the substance would visibly bubble inside the multicolored plastic casing. Their candle-flame shape, liquid movement and bright colors made them attractive, appealing, and potentially dangerous, especially for smaller children.

Methylene chloride is potentially toxic and can cause serious poisoning if inhaled, swallowed, or exposed to skin. If ingested the symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, headache, drowsiness, coma, seizures, heart attack, and even death.

Merry Christmas.

Obviously, accidents involving fires and electrical shocks were common during the early use of electric holiday lighting. In 1943, Bing “White Christmas” Crosby, famously lost his family home to a Christmas tree fire caused by faulty wiring.

Christmas tree lights were also notorious for constantly breaking down, and being difficult to troubleshoot and repair. In the 1950s and 1960s, an entire string of light sets would go completely dark when a single bulb failed. Finding the burned-out bulb wasn’t as bad as looking for a needle in a haystack, but close.

Today, electric holiday lighting has become an integral part of the holiday season in many parts of the world. Energy-efficient and cooler-running LED bulbs, improved wiring insulation, automatic timers, and safety certifications make today’s spectacular lighting options safer and more accessible than ever.

We hope your Christmas holiday is well-lit, safe and meaningful – stay grounded, too.