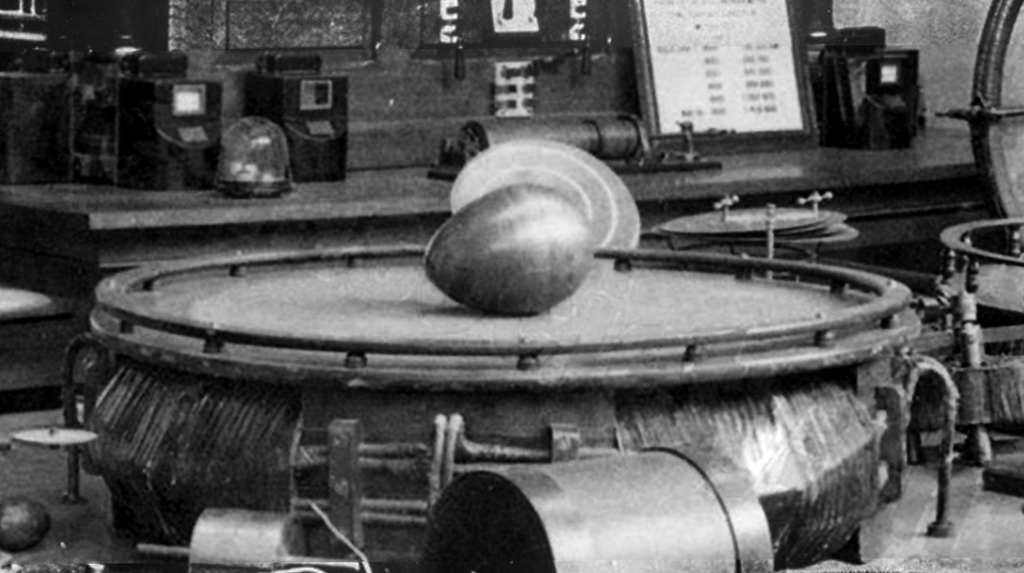

Of all the terrific artifacts and demonstrations featured at the SPARK Museum, we think the most clever is the recreation of Nikola Tesla’s famous Egg of Columbus display, featured in SPARK’s War of the Currents exhibit. The egg was inspired by the Italian explorer and guy who bumped into the New World four times and refused to acknowledge it, Christopher Columbus.

You might wonder why Columbus (1451-1506)—one of history’s biggest hot potatoes—even had an egg or what it has to do with Tesla’s brilliant and revolutionary invention. It’s a pretty good story, or stories, as there are more than a few, and frankly all are sketchy. Yet, myth or not, this colorful connection is surprising, and even inspired a variety of literary notables to think outside the egg.

But first, let’s do a little myth busting.

The biggest myth about Chistopher Columbus was he was trying to prove that the earth was not flat.

This is not correct, not even a little.

It was common knowledge in 15thcentury Europe that our planet was a big ball, just like all the other observable planets in our solar system. People not only knew the Earth was round, they also knew how far around. That’s right, way back in 1492 people knew the circumference of the Earth—and the Greeks had that same information over 1500 years before that. They measured the size of the Earth using the Sun, sticks & shadows, and good-old geometry. Their approximations were amazingly accurate.

That’s why Columbus decided to go west to get east. He was looking for a better trade route to east Asia, and wanted to avoid the many dangers, pitfalls, and complications of traveling back and forth from this profoundly remote, often treacherous part of the world.

The open water looked to be a safer option, and a more direct route to China, Japan and India. Trade with Asia offered low-born westerners like Columbus a shot at profound wealth, position, and fame.

So exactly what was so darn precious? Surprisingly enough, the answer is probably in your kitchen cupboard.

In 1492, the seasonings in your spice rack—especially cloves, cinnamon & nutmeg—were considered the most prized luxury goods of all, and nearly impossible to acquire. Pepper, cinnamon, and cloves came from the Indian sub-continent, cassia from China, ginger from southeast Asia, nutmeg came all the way from Indonesia’s tiny Banda Islands, later known as the Spice Islands. They were rare, exotic, delicious, healthful, medicinal, spiritual, and profoundly expensive, all from a remote, often perilous, faraway place hardly known to western civilization.

So, what’s the problem with sailing west to get east? The reason Columbus couldn’t find financial support to test out his theory was because everyone knew he would perish in the middle of the ocean before ever reaching Asia. It was too far and impossible to survive.

Columbus finally did get financial backing for his overly optimistic voyage and set sail for Asia. What he discovered surprised everyone. No, he didn’t sail off the edge of the planet, he didn’t die of thirst in the middle of the ocean, and he didn’t reach Japan or China or India.

Something even more remarkable happened. Columbus accidentally discovered a whole new continent (which he refused to believe, but that’s missing our point). Talk about the unexpected. It would be like flying to the Moon and bumping into another planet halfway there.

When Columbus returned to Spain he was greeted as a great hero and warmly received by his benefactors, Queen Isabella & King Ferdinand. Though Columbus brought no spices and little gold, he proved you could reach a new land by sailing west, offering Spain the promise of vast riches and unclaimed territories.

However, it cannot be said that everyone admired Columbus and his newly celebrated accomplishments. Many, particularly in the Spanish Court, were jealous and outwardly hostile toward the “Admiral of the Oceans”, a title his critics felt ridiculous, and worthy of public contempt. Which is where this story takes place, with Columbus facing down his critics before a gathering of the Spanish Court. The dialog went something like this:

“What has this pauper pilot done that was so great?” his critics asked. “Anyone can sail across the ocean. It’s the simplest thing in the world.” Columbus did not respond, but asked for an egg, placed it on a table, and challenged his critics, “Who among you can make this egg stand on end?” Everyone tried and no one succeeded. “It is impossible,” the Noble’s all pronounced.

Columbus then took the egg, gently tapped the end down on the table, creating a flat base, and presto, the egg stood up at full attention.

The Nobility felt tricked and cried “foul!” To which a triumphant Admiral of the Oceans replied: “What is easier to do than this, which you said was impossible?” Then added, “It is the simplest thing in the world, anybody can do it, after they have been shown how.”

There are a couple of versions of this story, but myth or not, it makes an excellent point. A new idea can seem impossible until demonstrated, then everyone thinks it’s obvious.

This story, and variations of it, has inspired more than a few literary giants, including Mary Shelley, in her 1818 novel The Modern Prometheus (aka Frankenstein), “In all matters of discovery and invention, even of those that appertain to the imagination, we are continually reminded of the story of Columbus and his egg.”

Leo Tolstoy mentions Columbus’s egg in War and Peace, (1869), “The spiritual guide was astonished at this solution, which had all the simplicity of Columbus’ egg.” Charles Darwin mentioned the “principle of Columbus & his egg” in his private autobiography (1887), and even F. Scott Fitzgerald refers to Columbus’ egg in The Great Gatsby (1925) when describing the East Egg and West Egg communities: “… like the egg in the Columbus story, they are both crushed flat at the contact end.”

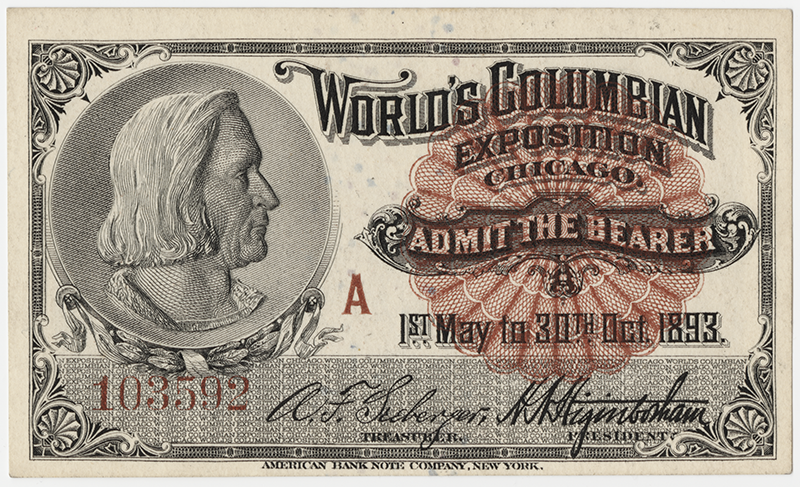

But the best example of a simple solution to an impossible problem is without a doubt Nikola Tesla’s graceful AC motor powered Egg of Columbus, featured at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ first contact with the New World.

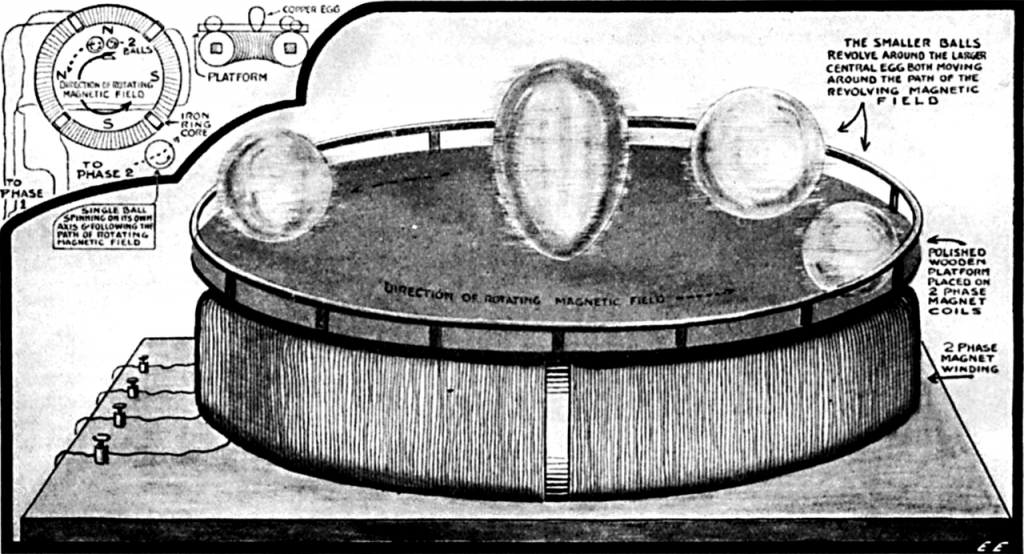

Tesla had harnessed the power of alternating current by producing a highly efficient induction motor, and wanted to show its superior power and durability. Inspired by the egg of Columbus story, and to help prospective investors grasp the potential of his AC motor, Tesla devised his own Egg of Columbus.

The original display consisted of a flat round wood surface surrounded by a slight lip. In the middle sat a large copper goose-sized egg. When the AC motor is turned-on, a rotating magnetic field is generated, causing the egg to spin just as any rotor in the induction motor would. As the copper egg gained speed, it lifts upright on its main axis.

“Up until this time, motors were smoky, noisy, and unreliable,” says John Jenkins, Museum President & CEO. “Tesla’s design was disarmingly simple, even elegant. It just hummed.”

Tesla sold the manufacturing rights to George Westinghouse, and helped set the stage to power and illuminate one of the largest, grandest public events in history.

On May 1, 1893, President Grover Cleveland touched a solid gold telegraph key igniting 12 seventy-five-ton dynamos and illuminating over 160,000 incandescent light and arc lamps. When it was over, more than 27 million people witnessed the greatest international event of its time—the successful electrification and illumination of Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition using Westinghouse’s alternating current electrical system.

“…the best result of the Columbian Exposition of 1893 was that it removed the last serious doubt of the usefulness to mankind of the Polyphase alternation current. The conclusive demonstration at Niagara was yet to be made, but the World’s Fair clinched the fact that it would be made, and so it marked an epoch in industrial history…” Henry G. Grout A Life of George Westinghouse.

Most of today’s the electric motors are based on the principles of a rotating magnetic field. AC technology is universally used to transport electricity from power generators to homes and businesses across the United States.

Tesla’s Egg of Columbus was a huge hit at the 1893 Fair, too bad you missed it. But you’re in luck: SPARK has a terrific interactive replica of the original Egg of Columbus in their War of the Currents Exhibit. We invite you to visit soon and feel a sense of wonder as you witness the effects of Tesla’s invisible rotating magnetic field.

“One demonstration is worth a thousand words,” says Jenkins.