This Thanksgiving an estimated 50 million turkeys will occupy center stage on dinner tables all across America. We’d like to take this opportunity to clarify some common misconceptions concerning that noble bird’s on again/off again relationship with our favorite Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin.

It’s safe to say that Ben and Tom share a complicated and disturbing history.

It is well documented that Franklin thought highly of the ‘Meleagris gallopavo’ (rough translation: guinea-fowl-pheasant). Though it’s untrue Franklin wanted the turkey to be our National bird, he did find it superior to the proposed bald eagle (which he thought looked like a turkey). Franklin went on to call the colorful poultry “respectable”, even “courageous…though a little vain and silly.”

Sounds good so for, but this is where things get uncomfortable, and where electricity comes into the story.

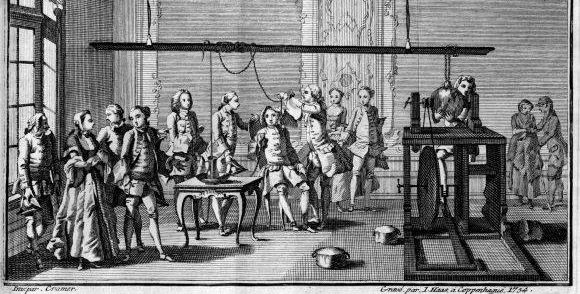

As we all know, Ben Franklin was an avid “electrician.” He began his fascination with static electricity as early as 1743, after witnessing a variety of electrical magic tricks performed by Dr. Archibald Spencer. Dr. Spencer was a sort of traveling showman whose demonstrations included suspending a boy from the ceiling and attracted feathers to his nose, and creating tiny sparks on the lips of statically charged lovers.

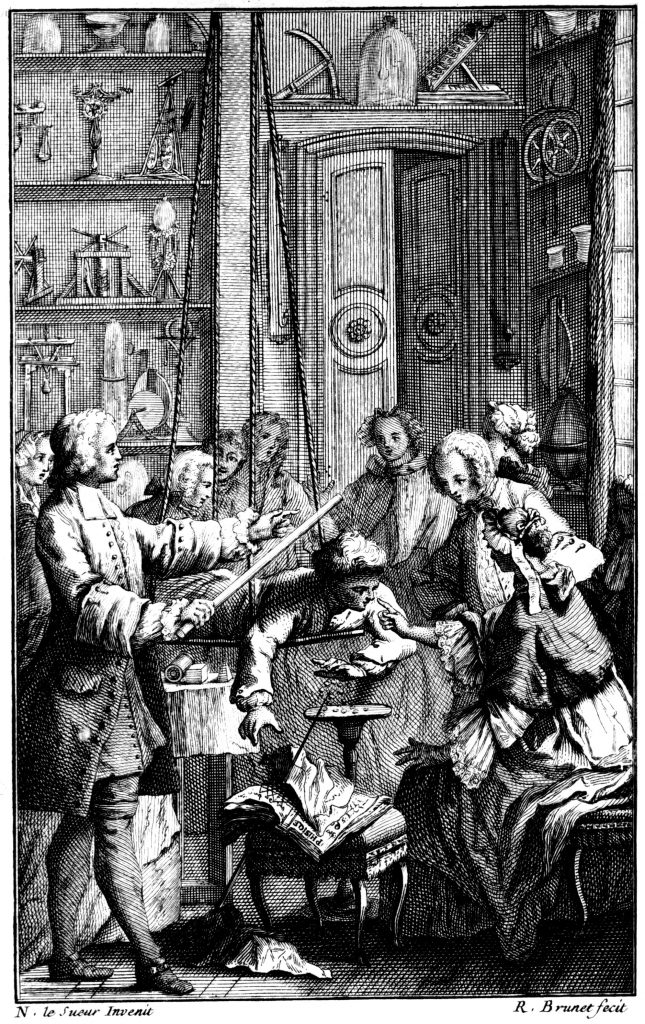

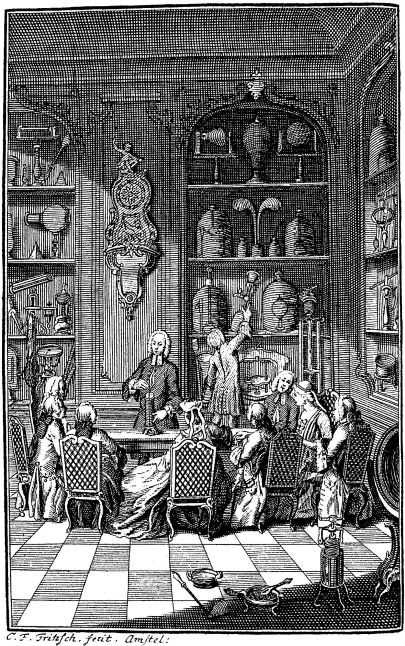

Franklin was enchanted with this new entertainment. Having recently retired from his printing business, he was able to devote much of his time experimenting and writing about the “electrical fire.”

“I never was before engaged in any study that so totally engrossed my attention and my time, as this has lately done,” Franklin wrote in a letter to Peter Collinson, thanking his English colleague for sending a Leyden jar, along with detailed instructions as to how to use it.

In the summer of 1749, Franklin wrote about hosting a somewhat hypothetical “electrical feast”, featuring a long list of electrically powered services beginning with electrocuting the main course–a turkey, then rotating the bird on an electrically powered jack over a fire ignited with an electric spark, and ultimately celebrated with electrified drinking glasses, giving everyone’s beverage an extra jolt when touched to their lips.

That extra jolt to their drinks might have felt necessary after seeing the host electrocute the main dish.

Why would Franklin do such a thing? Obviously the turkey has to be dispatched if it’s going to be the main course—something most of us aren’t required to do when considering a turkey dinner, but an electric shock?

Why would Franklin choose to administer the coup de grace via baby lightning? Was it more humane? Less messy?

Perhaps, but the real reason Ben Franklin preferred to shock his turkeys to death is because he loved them. Now when we say he loved turkey we don’t mean he thought they made great pets, or were really attractive, no, Franklin loved to eat them.

Franklin had a theory that shocking a live turkey with a strong electric charge would not only instantly kill the bird, but also tenderize it. He felt that the right amount of electric shock would vaporize and forcibly separate the particles of meat—much like the fibers of a tree struck by lightning—making it more tender.

By 1773 Franklin had vigorously tested his hypothesis, and in a letter, shared his detailed instructions for electrocuting and tenderizing a 10 pound turkey. By then Franklin had a battery of large glass Leyden jars, and was dialing-in the optimal amount of electric shock needed to kill and tenderize the animal.

Mistakes were made.

In some of his first attempts at turkey electrocution, Franklin applied too little a charge and only stunned the birds, who moments later stunned Franklin when they seemingly arose from the dead and regained consciousness.

It gets worse.

“I have lately made an experiment in electricity that I desire never to repeat.”

On December 25, 1750, Franklin, and his guests, got an unexpected surprise while attempting to electrocute a Christmas turkey. “Two nights ago, being about to kill a turkey by the shock from two large glass jars, containing as much electrical fire as forty common phials, I inadvertently took the whole through my own arms and body, by receiving the fire from the united top wires with one hand, while the other held a chain connected with the outsides of both jars.”

His guests heard a loud crack like the shot from a pistol, and reported to have seen a great flash as they saw their Host shocked senseless.

Franklin recovered from the shock, but never fully from the embarrassment. In a letter to his brother John, Franklin wrote: “Do not make it more public, for I am ashamed to have been guilty of so notorious a blunder.” Perhaps that is why, despite being a major contributor to the development and understanding of electricity, Franklin quietly dropped this particular line of research.

“The one who does the operation must be very aware, lest it happen to him, accidentally or inadvertently, to mortify his own flesh instead of that of his hen.”

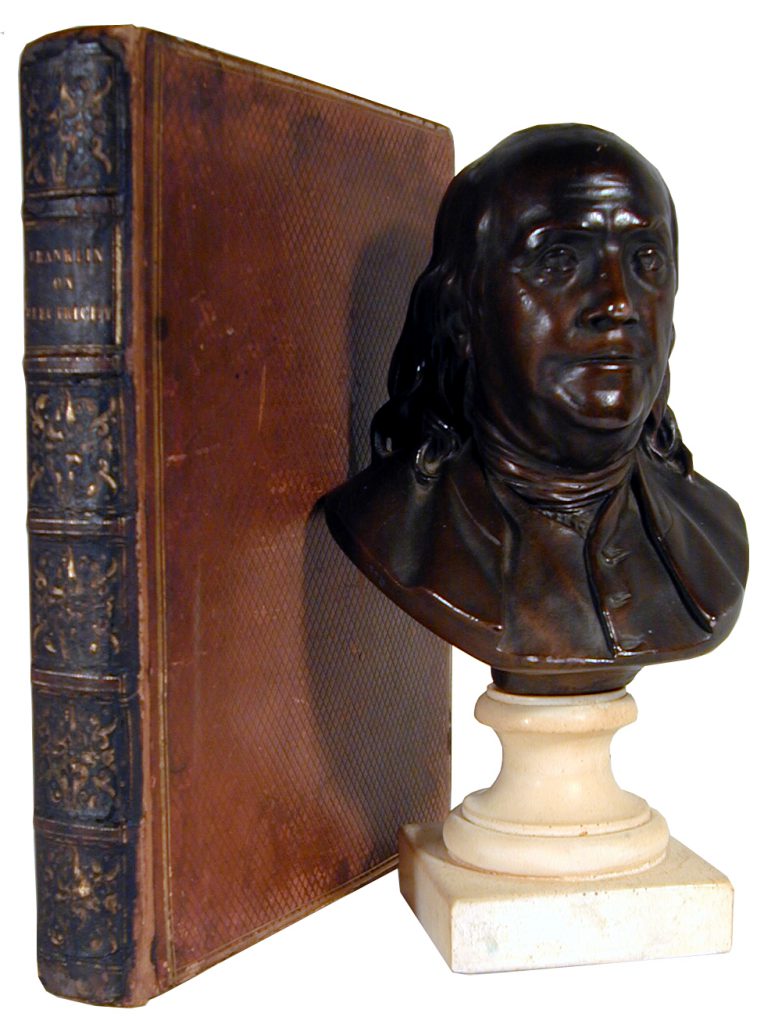

Franklin wrote about this, and other shocking discoveries in his letters, and in 1751 published ‘Experiments and Observations on Electricity,’ where an original copy resides in the Museum’s collection.