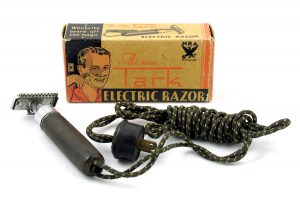

As electricity became more commonplace in homes throughout the United States, appliances proliferated. Toasters, curling irons, shaving razors, space heaters, clothing irons, electric fans, sewing machines and many more devices were touted as major improvements in homeowners’ quality of life.

A Hotpoint ad from 1919, for example, advertised coffee percolators, toasters and ovenettes that promised to “put an end to the hot, stuffy kitchen with the ever-present dirt, and the endless trouble and bother.”

However, it took more than 20 years after the introduction of home appliances for the industry to settle on what is so familiar today: two-pronged plugs (and, later, three-pronged grounded plugs) that could utilize wall outlets in convenient places throughout the home.

Like so much electrical history, the background behind this development is fascinating. Let’s take a look.

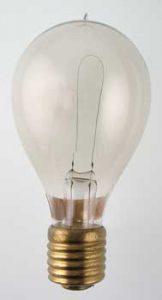

The incandescent light bulb was patented by Thomas Edison in 1880. Early bulbs had a variety of different bases, but by 1890, Edison’s familiar screw-type base – the one still in use today – had 70 percent of the market, according to an article by historian Fred Schroeder published in Technology and Culture. The Edison base was the de facto standard.

In the late 1800s, light bulbs were becoming common features in households across the country, along with Edison fixtures to hold those bulbs. But one thing Edison never really planned for was the explosion of household electrical appliances in need of electrical sources. As it pertained to toasters, vacuum cleaners and other such appliances, one big problem with Edison’s system was that light sockets were exactly where you’d expect them to be: high on the ceiling in the center of the room. Not exactly a convenient place for plugging in your new Hamilton Beach electric mixer.

Among the simplest ways of solving the problem was the introduction of extension cords, which could be draped from the center of the room over to the side table or kitchen counter. However, using an extension cord required unscrewing the light bulb to provide access for the cord. Not the best long-term solution.

But that wasn’t the only problem. What would happen if a clothing iron, say, that was plugged into the overhead light fixture, fell from the ironing board? A ripped cord and an electrical short were not unlikely results.

Harvey Hubbell, who in 1888 founded what today is known as Hubbell Incorporated, came up with an ingenious solution. Already known for his 1896 invention of the pull-chain electrical light socket, Hubbell devised a two-part device that would allow portable appliances to quickly pull away from light sockets. The base of the device screwed into the light socket, and a two-pronged plug cap that was connected to the appliance cord would allow the two to be easily separated.

An additional advantage of the Hubbell device – versions of which you can still find in hardware stores to this day, and even from the Hubbell website itself – was that the homeowner could leave the screw base installed in the fixture, only needing to plug in the cord when the appliance was needed. Voilà! How convenient.

Of course, the path from invention to acceptance wasn’t quite so simple, as Schroeder explains. Hubbell’s first plug cap device was patented in 1904, but it wasn’t until 1931 that wall plug receptacles had become common enough that the conversion was effectively complete.

Milestones during this process, according to Schroeder, were an agreement during World War I by six manufacturers to adopt the Hubbell design and a 1926 report by the National Electric Light Association’s Wiring Committee that all plugs by that point had become basically interchangeable, no matter the manufacturer.

Up to that point, there had been many competing plug styles in use. In fact, Hubbell himself had designed two styles – one with plugs in parallel and one with plugs in tandem, or on the same plane as each other. That’s why early wall receptacles featured T-shaped plug slots that would allow for the use of either style.

Though advertisements of the time still occasionally featured home appliances with Edison-type plugs, more and more – like the 1926 Hoover ad seen on this page, for example – began to show two-pronged plugs in use. Finally, the two-pronged appliance plug was here to stay.

Many of these devices are on display at SPARK Museum of Electrical Invention in downtown Bellingham. We look forward to reopening soon so you’re able to come and check them out. In the meantime, you might be interested in taking a Virtual Visit to SPARK Museum.