One of the best things about living in today’s world is having so much access to so much music. Whether streaming music on Spotify, purchasing songs on iTunes, or enjoying music videos on YouTube, your favorite music is accessible and available like never before. Frankly, for many of us, we can no longer imagine existing without the ability to carry our favorite music wherever we go.

Somehow, it now feels like our access to music is a birthright.

Unfortunately, it’s not. It’s hard to believe, especially for kids, but this amazing technology just got here.

Not long ago, there was no music. Well, there was music, if you made it yourself, or someone else performed it. Imagine, living in a time when the average person was lucky to hear a concert one or two times during their entire life. People didn’t have favorite musicians or bands they followed unless they were opera singers, marching bands or stage performers.

No radio or radio stations, no records or record players—no recorded sound at all. Nothing captured, no moment of inspiration preserved, nothing that can be repeated or shared. You had to be there. That’s the way it was, that’s the way it’s always been. Not long ago, if you wanted a machine that played your favorite song, it was called a music box.

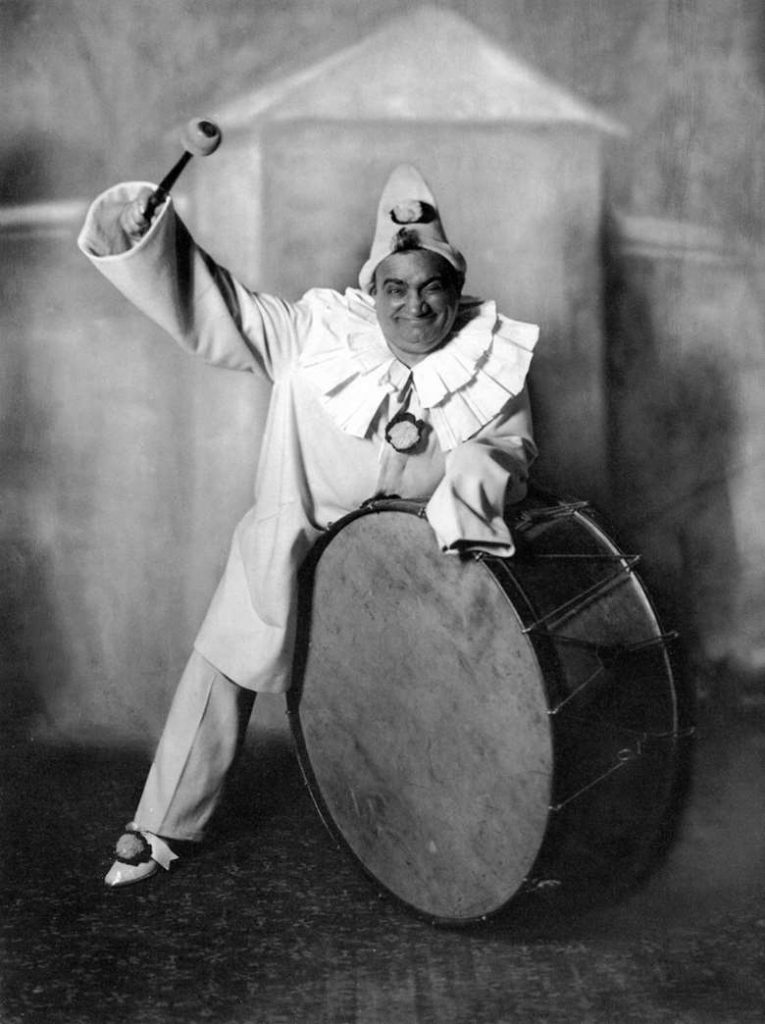

(1873-1921) became the first performer to sell over

a million copies of his recording of ‘Vesti La guibba’

In 1878, Thomas Edison changed all that by successfully recording sound onto a wax cylinder. The ability to capture and reproduce sound launched an entire new industry: The Music Industry. So marked the start of a massive shift in how people thought about and related to music—for the first time ever, people could hear music played without someone actually performing it in their presence.

Beginning around 1900, and for the next fifty years, the flat, 10-inch, 78 RPM record, was the music industry standard, and the first popular music distribution system. Soon millions of people were buying millions of 78 records and experiencing the world’s greatest entertainers performing popular songs in their very own home.

The new 78 RPM format was well received and generally worked fine, but quickly developed problems. To begin with the 78 discs were created using shellac: a hard, brittle material secreted by the female lac bug on trees from India and Thailand. Not only is shellac disgusting, but it also makes the discs heavy, fragile, cumbersome, and hard to preserve.

Even worse, the early phonographs—by today’s standards—sound terrible, with poor tone quality and lots of surface noise. Microphones weren’t yet in use, so recording meant musicians played into a huge, oversized horn, with the generated sound waves driving a needle that etched the song into wax. The reproduction—especially by today’s standards—is often inaudible.

As early as the 1930s the major record companies knew they had to replace the 78 record. Companies like Columbia and RCA experimented with a variety of advanced technologies and innovations; many new music formats were considered, including tape, wire, film, and even 16 & 20 inch transcriptions.

The Challenger

World War II put all major format changes on hold, but soon after the War ended, Columbia Records made the first move. In June 18, 1948, Columbia released the first long-playing microgroove non-breakable vinylite record, spinning at 33 1/3 RPM and holding about 23 minutes of music on each side.

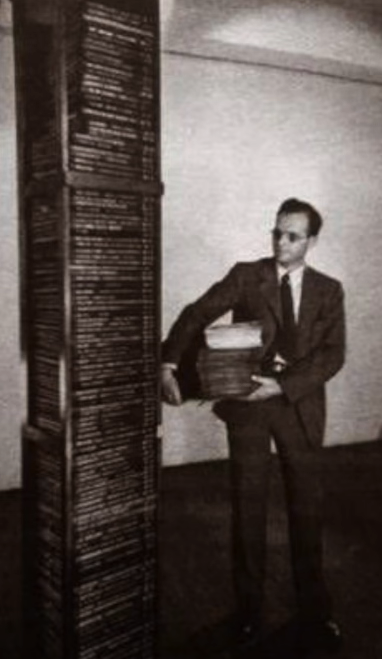

The new Vinylite (or vinyl) is much lighter, tougher and not nearly as gross as shellac. It’s also more durable, allowing grooves to be cut closer and increasing the disc’s capacity from 4 minutes, to over 20 minutes per side. At the official press conference a Columbia executive stood beside a 8-ft tall stack of 78s, while holding a 1-ft stack of LPs, both containing the same 101 albums of music.

Another advantage was the LP’s superior fidelity. It was a major improvement over 78s, with better range and tone quality, and much less surface noise. The LP created a new generation of audiophiles and music lovers who suddenly could appreciate and experience music on a completely new level.

The transition from 78s to LPs was also made easier since both records were about the same size and design. Soon record manufacturers were producing record players that played both 78 and 33 1/3 RPM speeds.

The Contender

RCA Victor wasn’t going to accept this news without a fight. Columbia and RCA were major competitors—and as if to add insult to injury, RCA had previously developed similar technology a decade earlier, but were unsuccessful, and let their patents expire. The thought of having to license the same format from their main rival was especially irksome, so RCA decided not to give in, but to challenge Columbia and their new LP format, and create something completely different.

On March 31, 1949, the RCA Company introduced the 45 RPM record, also known as a “single” or if you’re lucky, a “hit single”.

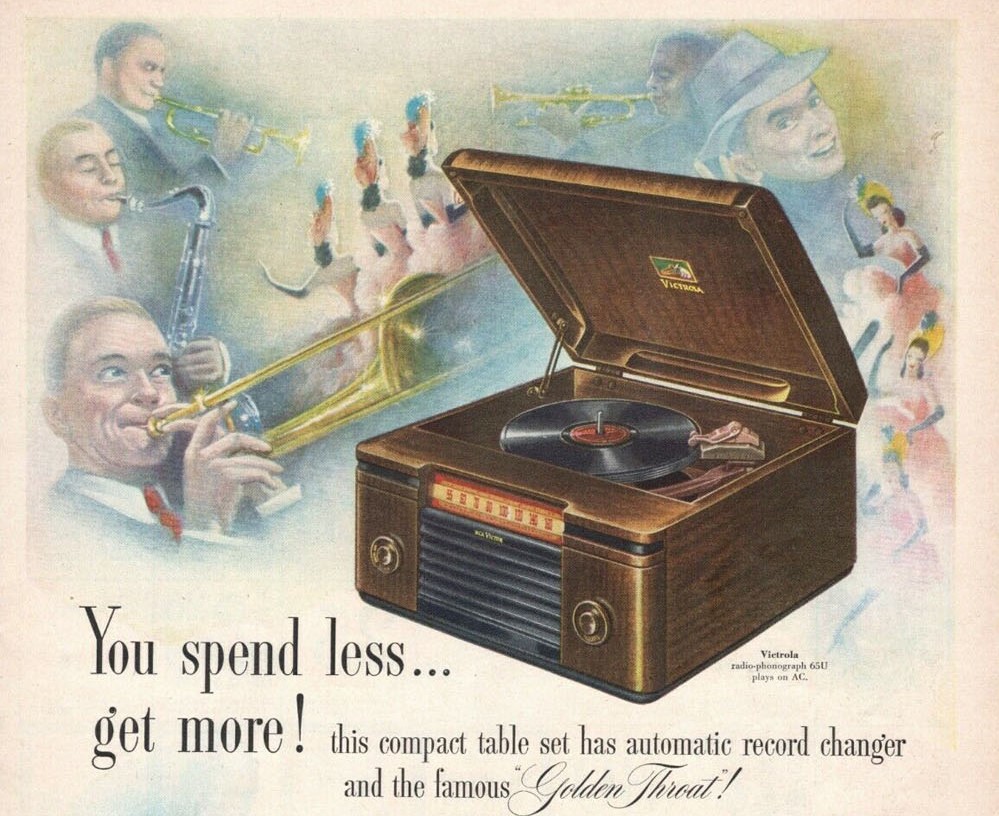

From the beginning, RCA was committed to the idea that a record should not need to hold more than one song. In order to make the disc smaller, they reduced the speed to 45 RPM, and used a much finer groove. As with the LP, they could pack in more grooves in a smaller space. They also used vinylite, creating much better fidelity. RCA boasted “Golden throat technology: ‘Critical listeners amazed at “Golden Throat” perfect tone reproduction.”

RCA also created a record-changer fast enough to essentially allow people to create their own long-playing musical experience. The large center spindle allows the 7-inch discs to handle easily and stack into place. Now listeners can create their own juke box, or playlist, right in their home.

Unfortunately, this means the listener needs to invest in completely new hardware. That was RCA’s plan, to manufacture a new type of proprietary turntable. It was compact, and featured their terrific new quick release disc changer. Can’t get it anywhere else. RCA Victor wanted the record purchasing public to make a choice, LP or 45.

So, what did people choose? Who won the battle of the speeds? Ultimately everybody won, and for different reasons.

Columbia won as their new 33 1/3 RPM LP was an instant hit with the listening public, and became the standard format for commercial recordings. More importantly, it ushered in the single disc, long playing album, which was perfect for classical music and Broadway cast recordings, greatly expanding and enhancing the musical experience.

However, the 45 RPM record won, too. It was cheaper to produce, easier to handle and easier to distribute to radio stations, making it perfect for popular music.

Shortly after the 45’s debut, record sales exploded with young people all across America embracing new music all their own. Suddenly songs like “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets were selling millions of copies, making the 45 the preferred format for distributing and playing pop music on top 40 radio, and by jukebox manufacturers and operators across the country. The 7-inch 45 RPM single would remain the heart and soul of the music industry for decades to come, with sales peaking at 200 million discs in 1974.

In 1982, the compact disc was introduced to the public, and soon vinyl would fall from grace, and no longer be music’s most popular form of distribution. Vinyl had its run, but if evolution teaches us anything, it’s that we are not the end, but yet another big step along the way.

Music technology may have progressed and moved on, but old school vinyl is still alive and thriving in a variety of niche collector markets. Today many top recording artists still issue their records on vinyl formats, if just to say they can. Some people say vinyl sounds better than other formats. We don’t know about that, but we do know it sure feels better. Looks better, too.

Don’t get us wrong, we love today’s technology and the almost countless conveniences it provides. We love our iTunes and our ear buds. We love the freedom, the choices, the mobility. And yet, it’s undeniable, the subtle thrill we always get when watching our favorite 45 spin in that little suitcase record player and hear the gentle hiss as the needle drops on the vinyl, and suddenly out pops Gene Autry’s voice, clear as a bell, filling the room with song.

Stay grounded.