In 2003—after over one hundred years of research and experimentation, after millions of miles of wire and cable strung all over the planet—wireless telegraphy had finally become the dominant force in telecommunications. For the first time since its introduction in 1892, the land-line telephone had dropped in world-wide popularity and has been dropping like a rock ever since.

Inventors and visionaries have always dreamed of communicating from afar. People have used smoke signals, mirrors, drums, birds and flags to send messages from one point to another. Both the electric telegraph and telephone transformed communications in the 1800s, and at the close of the century radio was poised to start a third revolution.

Some of the earliest speculation about radio’s future centered on the almost mystical idea of portable individual communication. “A number of scientists scattered all over the civilized world are eagerly seeking a solution to the problem of wireless telephony,” states an early enthusiast in The Electrician (1902). “A future generation may conceivably accomplish as much in wireless telephony as is dreamed of today by visionaries.”

In 1905 the wireless telephone’s leading visionary was the prophetic writer and inventor A. Frederick Collins. At the beginning of the 20th century it was Collins who was poised to solve the mysteries of receiving and sending messages without wires. And why not? By 1905, at the age of 36, Collins had already published scores of articles for serious science and trade journals, as well as several bestselling wireless books including “Wireless Telegraphy: Its History and Practice” 1905.

“The most authoritative and complete work on the phenomenon of wireless telegraphy in the world,” states the original book jacket. A. Frederick Collins was considered the authority on wireless communication and when he first demonstrated the Collins Wireless Telephone the established telephone companies of the day (Bell) instantly went into a panic, with the realization that their newly installed land-line phone system was already a dinosaur and soon to be out of business. Their research departments frantically tried to duplicate Collins’ incredible wireless demonstrations.

The Collins name had become synonymous with wireless telegraph and telephone. His theories and inventions regarding wireless were mind-boggling to a world only beginning to grasp the far reaching implications of telecommunication. “It is now possible to talk without the use of wires with persons in opposite parts of a building regardless of walls or distance,” he wrote in 1905. This was just the beginning, he insisted. “Soon, people all over the world will be speaking to one another without the use of wires.”

At the same time, men like Edison, Marconi and Tesla were working intensely to make wireless a commercially viable alternative to the wired telegraph. Several of these technical visionaries formed partnerships with businessmen of questionable character—men more interested in making a killing in wireless stock speculation than building successful companies. Collins was certainly no exception.

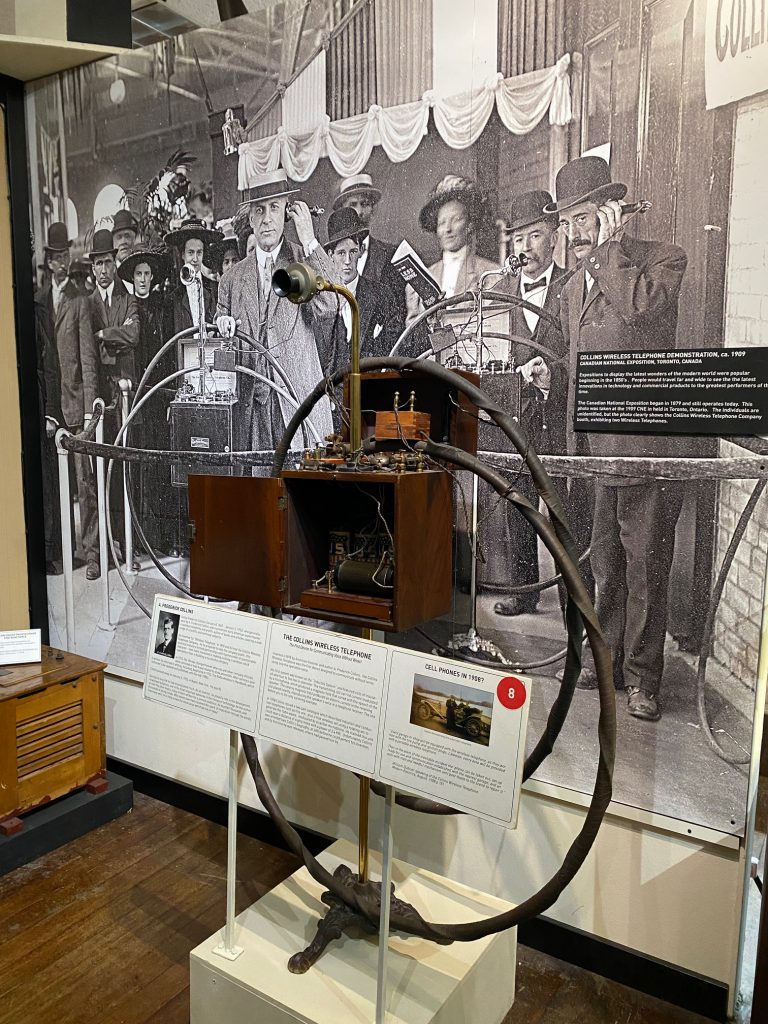

Collins, along with a small group of such businessmen wanted to take wireless to the next logical step—wireless telephone. In 1903 he formed The Collins Wireless Telephone Co. Soon Collins was touring the country and Far East, performing wondrous demonstrations, and selling tons of stock in his new wireless telephone company.

Collins claimed his wireless telephone would go where wires could not. “Every auto will be provided with a portable wireless telephone in order to call for help if the car were to breakdown,” wrote Winston Farwell in Technical World Magazine, (1909). “One may take a wireless telephone on an automobile, a motorboat, an airship or submarine, into a tunnel or a mine and be able to converse with others as freely and as plainly as one can now talk over a local telephone with nearby points.”

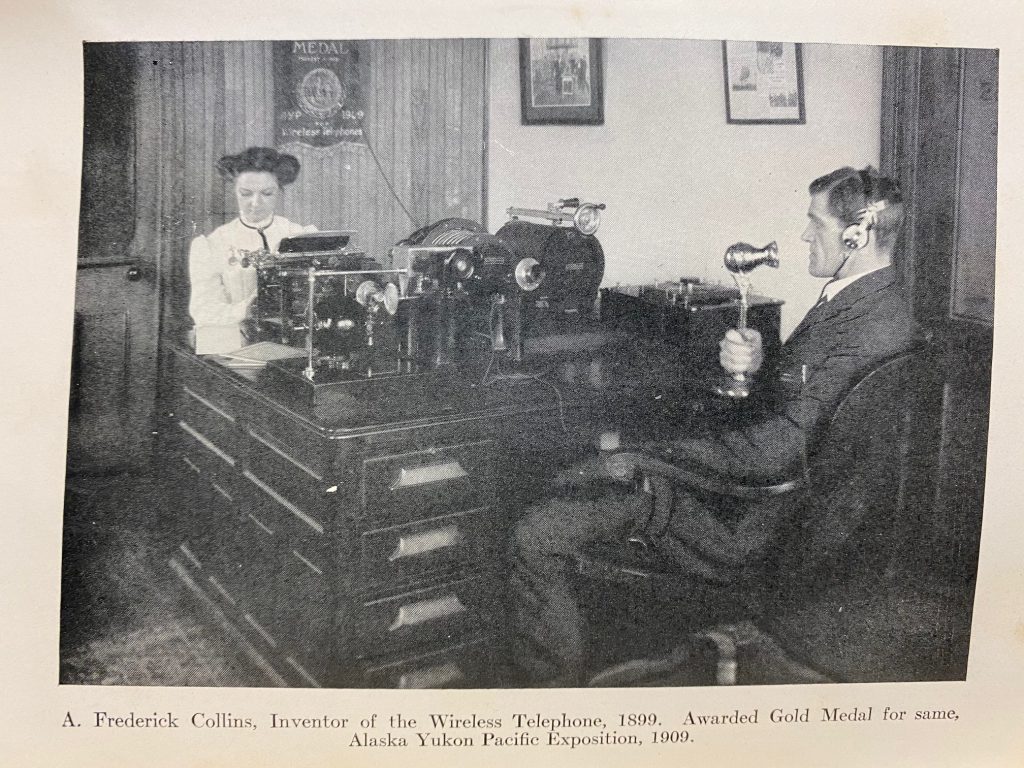

That same year Collins’ wireless telephone won the gold medal at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle. There were plans to equip all vessels in the US Navy with his wireless telephones. He continued to write and publish his promise to soon connect the world with his wireless communication equipment.

But by 1911 the lack of progress had triggered widespread skepticism. One day, it was discovered the demonstrations were prearranged and a hoax. Collins’ associates would rent two adjoining rooms in a hotel for the demonstrations, placing the coils on opposite sides of the wall. Then they would invite celebrities and government officials to demonstrate the apparatus. These demonstrations were spectacular and resulted in impressive stock sales.

In December, 1911, four officers of the Collins Wireless Telephone Co. (now known as The Continental Co.) were indicted for using the mail to defraud by selling worthless stock. In addition, Frederick Collins was charged with giving a fraudulent demonstration of his wireless telephone on October 14th, 1909 at the Electrical Show in Madison Square Garden, for the purpose of selling stock in his company. The world’s foremost expert on wireless telephony was now painted as an imposter and a fraud.

In 1911, A. Frederick Collins was sentenced to three years in prison in Atlanta. After serving one year he was released on parole. Before his conviction he had been a respected engineer, considered the authority on wireless in general and a specialist in wireless telephony. His loss of credibility must have been devastation.

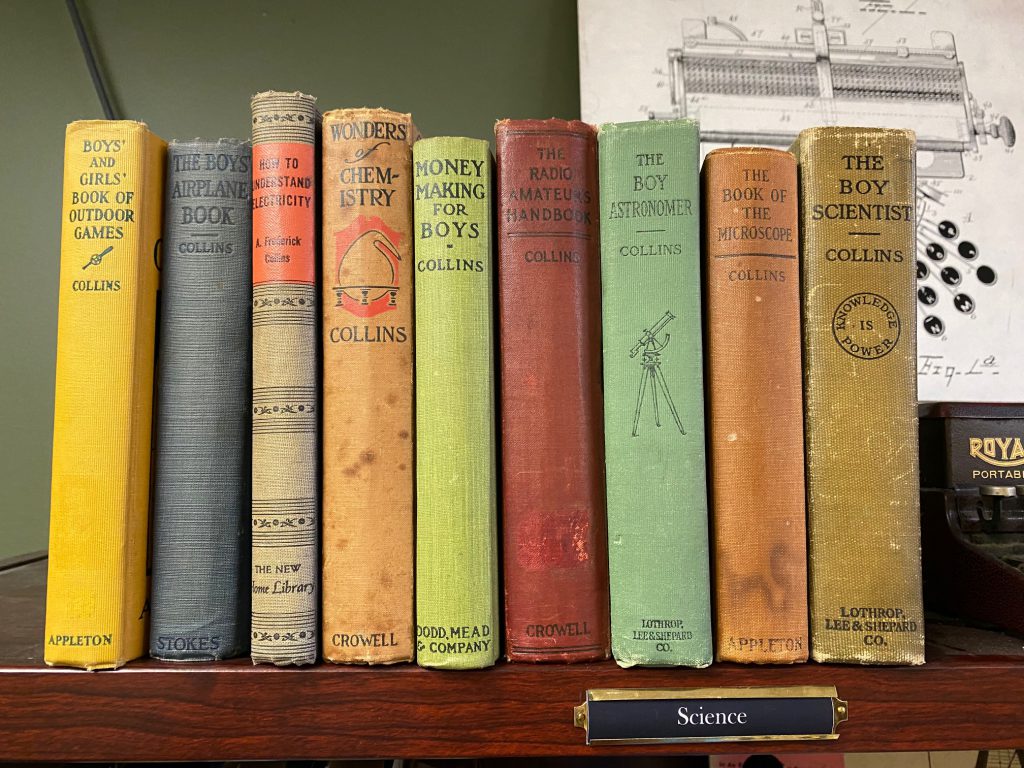

Somehow he went on. Collins gave up his controversial pursuit of wireless telephony and assumed a quieter, more reserved life in the greater New York area. Over the next thirty-five years, Collins published a continuous string of over one hundred books for children and young adults dealing primarily with basic science and electricity, including the Collins Radio Amateur’s Handbook, still considered the best all-around introduction to radio and its operation ever written.

In 1910, the Encyclopedia American and many other scientific publications, placed Collins in a class with Franklin, Morse, Bell, Edison and another inventor keenly interested in wireless: Marconi. Today, Collins is all but forgotten. It’s almost impossible to find his name anywhere. The exact date and place of his death are still mysteries. All that remains of Collins incredible life’s work is on display at the SPARK Museum, who possesses the largest collection of A. Fredrick Collins artifacts, books and memorabilia anywhere, including the actual wireless telephone used in the fraudulent demonstrations.