IT WAS A WESTERN ELECTRIC MODEL 20L – the most common candlestick phone on the market. It looked pretty much like any other candlestick phone – the type used by Sam spade in the Maltese Falcon – but this one had a small brass plaque attached to the neck which read:

“This instrument used by Maj.Henry L. Higginson at Boston, Mass. to open the Transcontinental telephone line with Thomas A. Watson at San Francisco, Cal. Monday evening January 25, 1915. Transmitter cutout & signal buttons added”

Intrigued, I asked the owner about it. He said it was sold to him by another collector who had obtained it from a relative of Higginson. I hadn’t heard of Higginson, and knew little about the transcontinental telephone line. But this was too good to pass up, so I bought the phone and began my research.

Henry Higginson

Henry Lee Higginson was a noted Bostonian banker and Philanthropist. As a young man during the Civil War, he and his seven friends joined the army, where he served with distinction and attained the rank of Major. Six of the seven friends were killed in the war, a terrible personal loss that would profoundly shape the rest of his life.

An avid music lover, Henry Lee Higginson founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1881 and was its chief benefactor. In 1890, by now a successful banker, Higginson donated 31 acres to Harvard University. He dedicated the gift to his fallen friends, asking that the property be called “Soldiers Field.” Today, a large marble marker at the field’s entrance recognizes Higginson’s gift, and the friends that he held so dear.

Higginson’s philanthropy was deeply rooted in the sense of honor he felt for his lost friends. In a letter to Historian James Ford Rhodes, he said: “If my nearest and dearest playmates had lived, they would have tried to help their fellows, and as they have gone before us, the greater need for me to try – and the many tasks are still before us …”

Higginson’s connection to the telephone came through the business of his firm, Lee, Higginson and Company. Because the firm was one of the early financial backers of American Bell (which became American Telephone and Telegraph in 1900), Higginson was invited to participate in the events around the first transcontinental telephone call. The call took place between New York and San Francisco on January 25, 1915.

The Transcontinental Telephone line

The transcontinental telephone line linking the Atlantic seaboard with the West Coast was completed in the summer of 1914. Over 13,600 miles of No. 8 copper wire were laid; four wires crossing 13 states on 130,000 poles. Six repeater stations featuring the new De Forest audion vacuum tube amplifier were required to maintain the signal at acceptable levels. The rate for a three-minute call: $20.70

Strict orders were given that AT&T president Theodore Vail’s voice must be the first to be heard across the line. This led to some very creative testing procedures, which ensured no single engineers’ voice was carried coast to coast. Finally, on July 29, 1914, with little fanfare, Vail spoke the first words to be heard across the continent. Officials had planned for the launch of the new line to coincide with the opening of the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, but since the line was finished a few months early, the public event opening the line had to wait.

The Panama-Pacific Exposition

In 1906 San Francisco was devastated by a great earthquake and fire. Only nine years later, the Panama-Pacific Exposition opened its gates – not so much as a tribute to the completion of the Panama Canal as it was a grand celebration of the rebirth of the city. And grand it was. The 11 exhibit palaces covered over 64 acres. An actual Ford assembly line was set up in the Palace of Transportation and turned out one shiny black Model-T every 10 minutes for three hours every afternoon. The entire area was illuminated by the latest developments in indirect lighting by General Electric. Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and other greats were seen frequenting the grounds of the fair. On opening day, President Woodrow Wilson used a wireless apparatus from his office in Washington D.C. to start the Diesel-driven generator that supplied all of the direct current used in the Palace. There was excitement and wonder in the air.

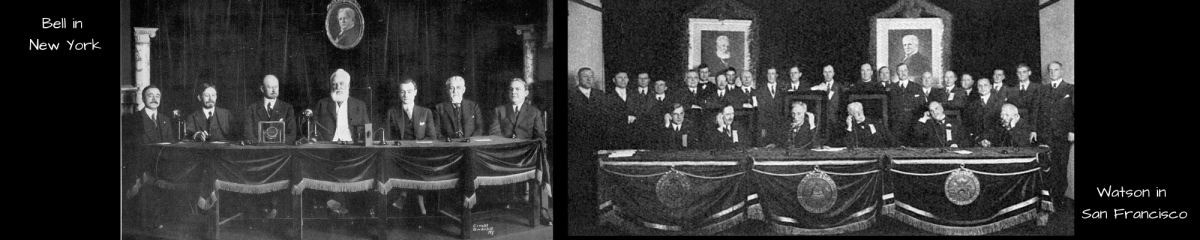

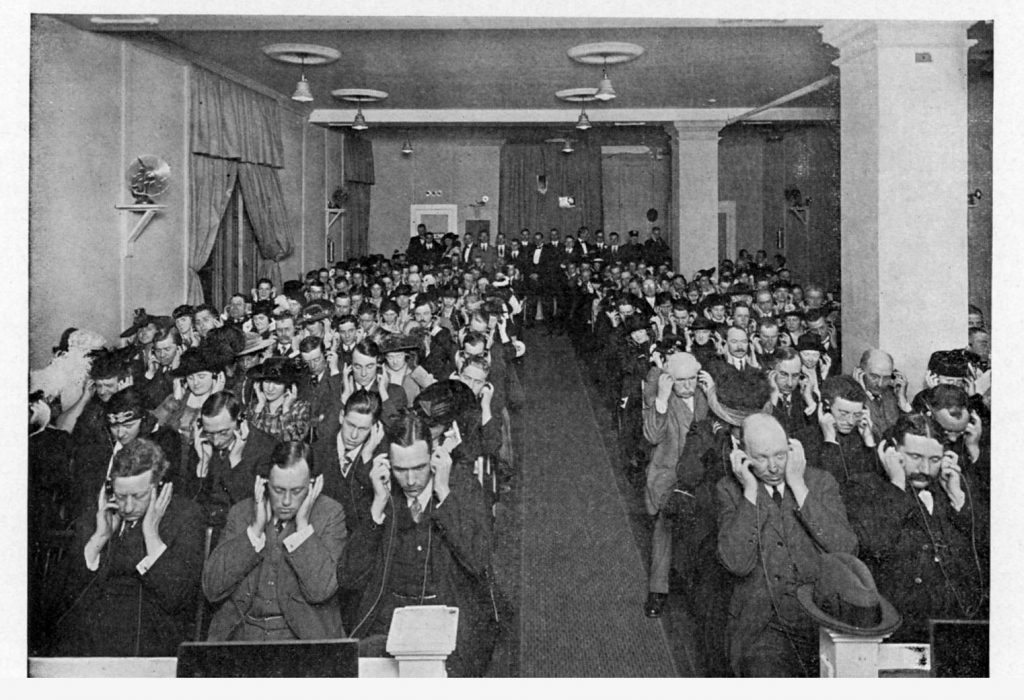

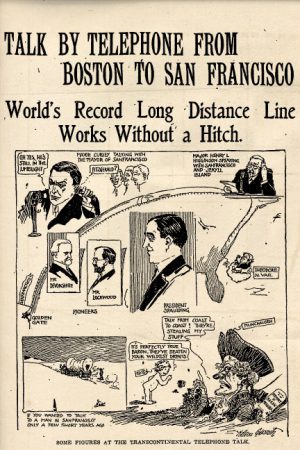

The magic continued on January 25, 1915, when the 3.400 miles separating New York and San Francisco suddenly vanished as the transcontinental telephone line was officially opened for business. Thomas Watson, Alexander Graham Bell’s former assistant, assembled with a group of dignitaries at the Expo’s AT&T theatre, while Bell led a similar group in New York. Audience members at both locations were each provided a set of headphones, giving them a firsthand opportunity to listen in.

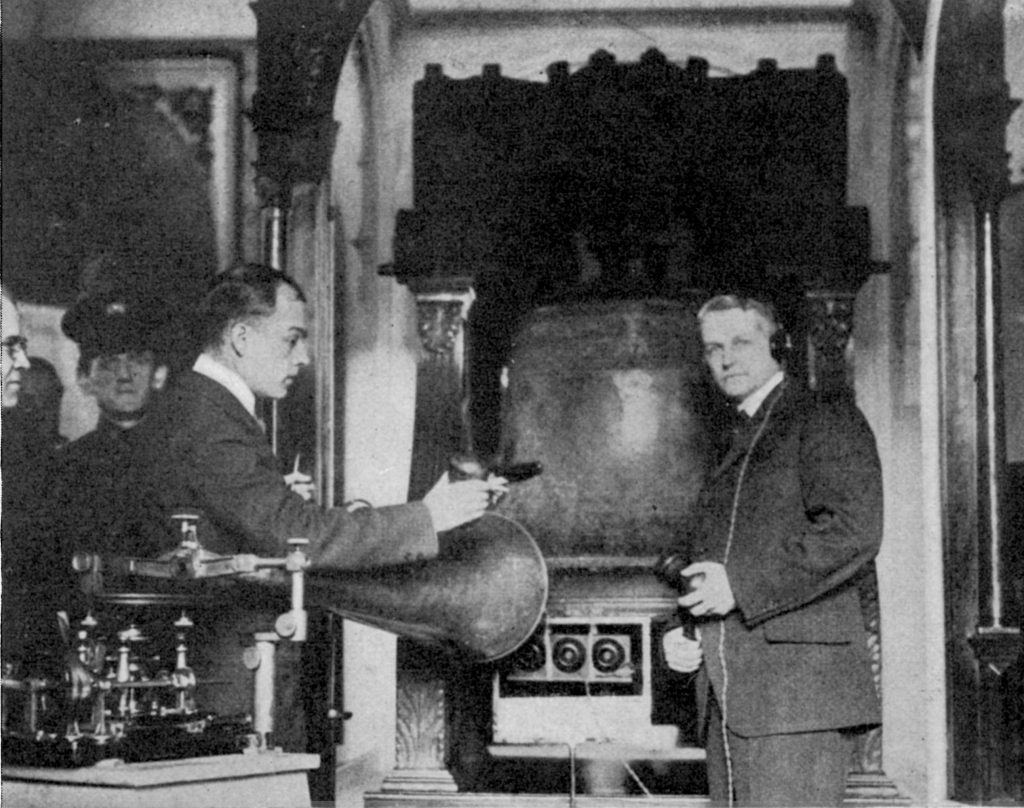

At 4:30 PM in New York, Dr. Bell lifted the receiver and began a conversation with Thomas Watson.

“Hoy! Hoy! Mr. Watson! Are you there? Do you hear me?”

“Yes, Dr. Bell, I hear you perfectly, do you hear me well?”

“Yes! Your voice is perfectly distinct. “

Later in the call, AT&T President Theodore Vail spoke from Jekyll Island, Ga., and President Wilson offered his thanks and congratulations from the White house. The call continued for some time, with congratulatory speeches and conversations from officials on both coasts. At one point during the call, someone asked Professor Bell if he would repeat the first words he ever said over the telephone. He obliged, picking up the phone and repeating “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” To which Watson, in San Francisco, replied, “It would take me a week now!”

Henry Lee Higginson and a group of officials waited in Boston. In front of them sat the latest in telephone technology, a Western Electric Model 20AL desk telephone. At 8:00 PM eastern time, Higginson picked up the phone and placed a call to Watson waiting in San Francisco. After exchanging pleasantries, Higginson handed the phone to Boston Mayor James M. Curley, who spoke with his counterpart, San Francisco Mayor James Rolph. Theodore Vail again joined in from Jekyll Island, and a host of other officials took their turn at participating in this historic event.

The opening events were only a prelude. Exhibitions and demonstrations were staged daily and included remote “conversations” with famous people such as Thomas Edison, Admiral Peary, and many others. An Indian chief spoke from Winnemucca, Nevada, and two Chinese exchanged greetings in their native tongue, offering a simple but effective demonstration that the line could transmit a foreign language. Visitors were also treated to the sound of the surf crashing on the rocks of the Atlantic Ocean. One of the most impressive demonstrations took place in Independence Hall, Philadelphia. A telephone transmitter was placed inside the Liberty Bell, and when it was tapped with wooden mallets, the ring of the old bell was heard in San Francisco. It broke a silence of 80 years; the bell having cracked while tolling the death of Chief Justice Marshall in 1835.

The transcontinental telephone line show at the AT&T theatre would be one of the most popular exhibits of the fair, from opening day until the gates closed on December 4th, 1915. Following the fair, the line continued to capture the public’s imagination as heard in The Ziegfeld Follies’ “Hello, Frisco,” the most popular tune of 1915.

Western Electric 20AL telephones, like the one Higginson used, were introduced in 1915 and made by the millions. But a small brass plaque attached to the neck makes this one unique: A tribute to that magical day when east met west, when the peal of an historic old bell in Philadelphia was heard all the way to San Francisco – the opening of the transcontinental telephone line.

Source:

Where Discovery Sparks Imagination: A Pictorial History of Radio and Electricity

by John D. Jenkins

https://smile.amazon.com/dp/1518780520/ref=cm_sw_em_r_mt_dp_7DC4MQTTB33A692MX34Y