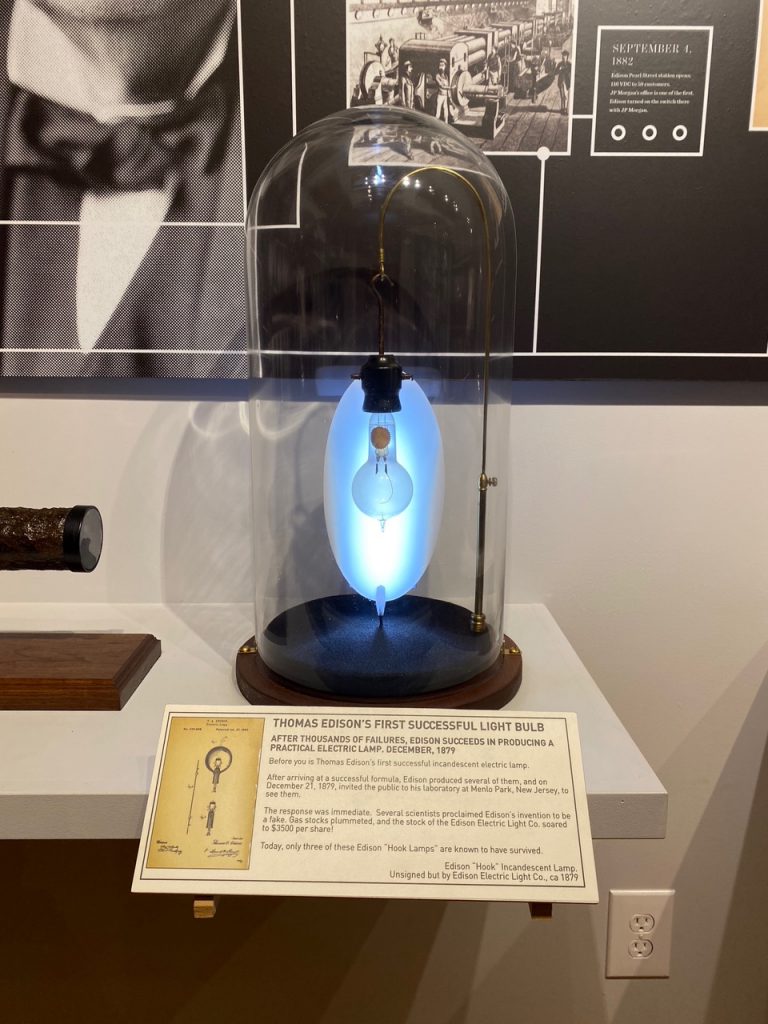

On permanent display in the Museum’s War of the Currents Exhibit.)

Whenever folks are asked to think of something useful that uses electricity, the lightbulb is almost always an immediate response. You remember, those round little bulbs with the wires inside—those little ships-in-a-bottle—that can burn the prints right off your fingertips?

To put it simply, we think the lightbulb is the greatest electrical appliance ever created, and with good reason. It represents something people have wanted and valued since the dawn of humanity, something fundamental, a discovery responsible for expanding and transforming our world: artificial light.

Unlike every other lamp before it, the electric lamp does not burn combustibles like oil or gas – no this lamp is lit with ‘electric fire’, and offered Americans a brighter, cleaning, smarter future.

Since its introduction in 1879, the lightbulb has been a symbol of progress and enlightened thinking. It was the lightbulb (along with Westinghouse’s AC distribution system) that ultimately brought affordable, accessible light to Americans across the nation—and at a time when quality artificial light was a luxury few homes and businesses could afford.

If you could fly over the United States in 1879 (hot air balloon?), you’d be flying over a very dark, cold planet, primarily lit by the sun, and when the sun went down, humanity went down too, got huddled-up for warmth and protection (“It’s pretty dark out there”), and if people were lucky, they produced their own light: fire.

Fire, humanity’s first great giver of artificial light. One can imagine going back in time, even a few hundred years, when having a torch at night was like having a tiny burning sun glowing on the end of stick, leading you bravely through the otherwise pitch-dark world.

It didn’t matter if you wanted light in the year 1879 BC or the year 1879 AD you still relied on oil, wax, coal, wood and later gas. They all worked, some better than others. All were smelly, smoky, costly, and often too hot to handle (making whale oil particularly valuable as it burned cleaner and longer than other combustibles, and afforded only to wealthy kings and queens – and whale men).

Accidental fires were a common occurrence, especially in cities and other densely population areas. Fire was deadly and everybody knew it. Fire was a dangerous necessity, and a fact of life.

So you’d think Americans would be clamoring for the chance at switching from combustibles to no fire, no smoke, no smell electrical power. You’d think families would be thrilled to flow rivers of continuous electricity into their bedrooms and kitchens and bathrooms.

Well, they were not thrilled, because even in 1879, people knew enough about electricity to know it was dangerous, even lethal. And as much as people needed light, they weren’t convinced electricity was the best way to get it.

Take a bolt of lightning,for example. In 1879 you didn’t have to be Benjamin Franklin to know lightning could be extremely dangerous, striking an average of about 25 million times a year in this country alone. Many Americans had witnessed first-hand the profound, sometimes devastating effects of a single strike of lightning. The idea of controlling that same force (baby lightning?) and running it continuously throughout American homes and businesses seemed questionable to say the least.

“What had God wrought?” Samuel Morse, 1844

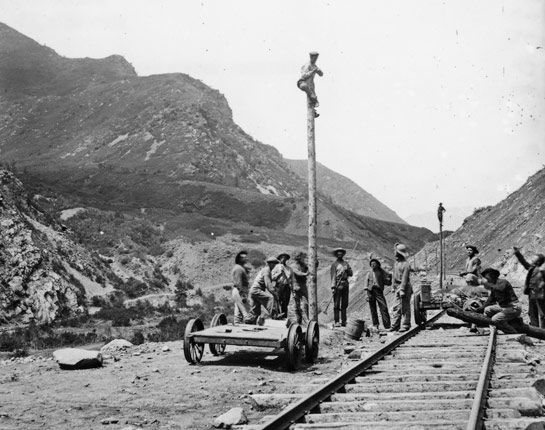

Decades before the debate and introduction of the electric light, many American cities and businesses were already wired up with telegraph and telephone communication systems. Not only did the first electric telegraph system allow messages to be sent hundreds of miles in a matter of seconds, but without the telegraph there would be no safe, reliable train travel. Both the telegraph and train travel went hand-in-hand, allowing information, and people to travel great distances faster and more securely than ever before.

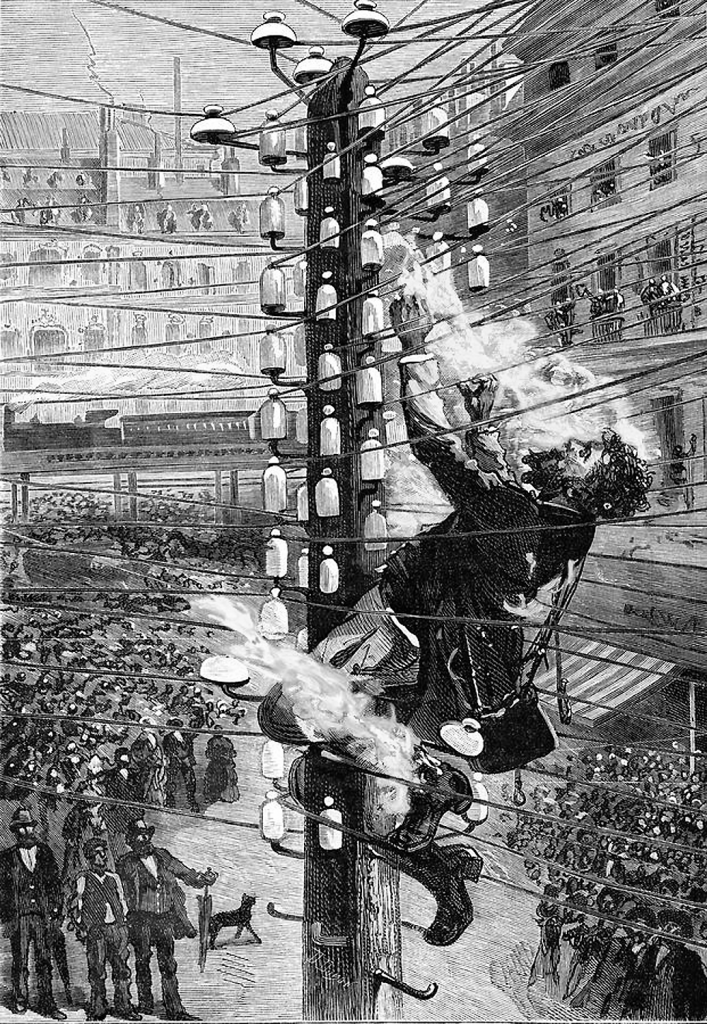

But this new ability to communicate and travel came at a cost. In the late 19t century many of American’s city skylines were filled with hundreds of telegraph and telephone communication wires criss crossing and choking off the view.

And yes, they were dangerous.

One of the most dramatic examples occurred on October 11, 1889, when John Feeks, a Western Union lineman, got tangled in a clump of wires and cables while trying to repair a telegraph line in downtown Manhattan. When Feeks accidentally grabbed the wrong wire he unknowingly offered the electric charge a path of least resistance, jumping from his hand, through his body, and shot out his steel-studded electrician’s boot. He was said to have been killed almost instantly (inspiration for the electric chair?), but his body, still tangled in the wires, continued to twitch, spark and smolder—like a ragdoll’s dance of death—while horrified New Yorkers stood transfixed, barely able to finish their pastrami on rye.

Downtown dinner and a show.

Accidents like this made most Americans uneasy with the thought of electrical power. Yet just four short years later over 27 million people would visit the historic 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where AC electricity safely illuminated over 200 buildings inside and out with bright, clean, White City light. No smoke, no soot, just clean, bright night at the flip of a switch. After Americans were able to safely experience first-hand the obvious benefits of electric lighting there was no going back, and the goal of distributing electricity to every home and business in the nation had begun.

NEXT MONTH~ Question: What does the electric chair, a bolt of lightning, and your toaster all have in common? Tune in next month to read the shocking results!