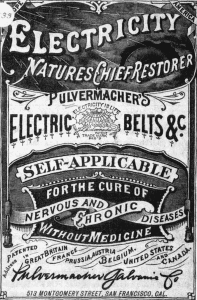

“Electricity: Nature’s Chief Restorer.”

The words undulate across a backdrop of jagged lightning bolts and stormy skies in a brazen advertisement for Pulvermacher’s Electric Belts. It’s a bold piece of advertising — not only in its design, but also in its claims.

“Self-applicable for the cure of nervous and chronic diseases without medicine.”

Pulvermacher’s electric belts — one of which is on display at SPARK Museum of Electrical Invention — contained a copper disc in the front with two to four chrome-plated nickel discs at the rear. The “copper-nickel interaction” supposedly created a healing electromagnetic field that would treat almost any disease by magnetizing iron in the blood, thus improving oxygenation to all tissues. Separate belts were available for both males and females, with the male version containing a suspensory attachment for improved potency.

The early days of electricity were interesting times.

“As electricity became an increasing part of the daily lives of the average person in the 1800s, there was a natural curiosity about its possible curative powers,” says Tana Granack, director of operations here at SPARK Museum in Bellingham. “Some people, either well-meaning or outright dishonest, took advantage of this and invented devices and systems that claimed to cure a variety of illnesses through a jolt of electricity. Just the right amount in just the right place. And if you feel it, it’s working.”

Except that, of course, it wasn’t.

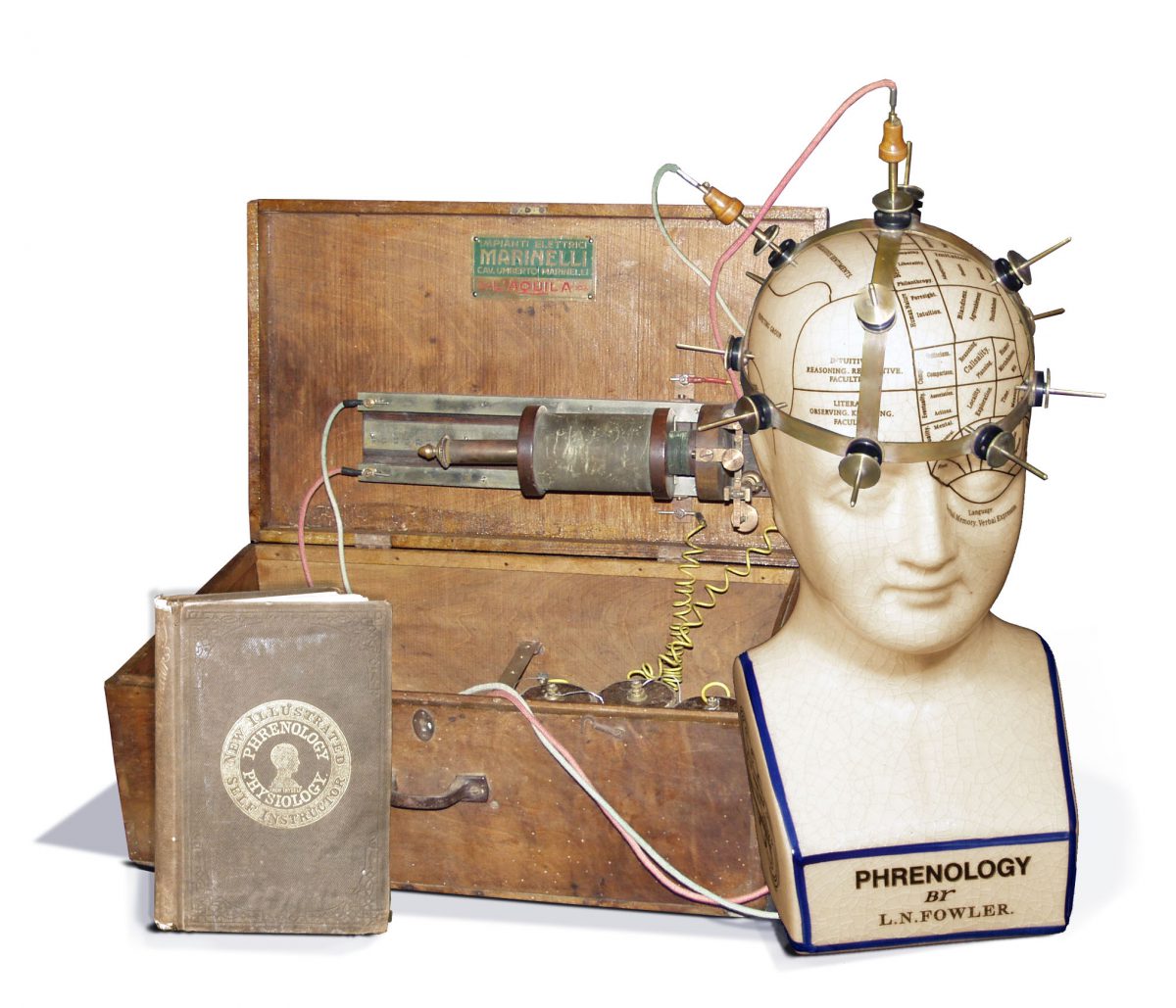

Consider the “science” of phrenology, which was all the rage in the 1800s. The basic idea of phrenology was that a person’s personality traits, such as kindness, benevolence and mirth, could be predicted by feeling the bumps on the person’s head.

Electric “scientists” got into the act by creating electric phrenology helmets that could apply electricity to those areas of the head corresponding to desired traits. A little jolt for more self-esteem here, a tinge of electricity for more friendship there.

On display here at our Bellingham museum is one such device from the late 19th century. A wooden box houses a sledge induction coil and three batteries to power the device. The electrical phrenology helmet itself contains 13 brass electrodes, each 3 inches in length, evenly spaced across the crown. This extremely rare device sits on a phrenology bust devised by Orson Squire Fowler and his brother Lorenzo Niles Fowler, a couple of quack medical charlatans who were largely responsible for the whole phrenology craze.

The basic idea, which is credited to Francis Gall in 1796, sounds plausible. Gall theorized that brain areas should grow when exercised, like muscles. And what better to “animate” areas of the brain than the new magic wonder of electricity!

But here’s the deal, Granack says: Science can only answer so many questions. The Fowlers, like Pulvermacher and so many others, knew that and capitalized on it.

A fake pill or treatment, called a placebo, can accommodate for a third of cures, Granack says. Another third of patients naturally recover from most aliments, at least temporarily, without needing intervention. That’s a two-thirds basic success rate.

“No wonder quacks get away with so much then and today,” Granack says. “Some things are hard to prove, especially when the patient thinks the electric charge is curing things that are hard to measure, that are more subjective — like depression, anxiety or pain. Placebo has made a lot of people a lot of money.”

So something seemingly magical, like electricity, was easy to sell as a special cure for ailments. People wanted it to work, they didn’t understand it, and it was hard to disprove. Consider this quote from an 1800s ad for Dr. Scott’s Electric Flesh Brush: “It opens the circulation, opens the pores and enables the system to throw off those impurities which cause disease.”

Um, sure.

(However, it is worth noting that several early approaches to healing with electricity have since been proven to work, and electrotherapy – the application of low-level electrical current to the body – is now an important part of mainstream medicine. Examples include pain management, treatment of neuromuscular dysfunction, tissue repair, improving peripheral blood flow, parasympathetic nerve stimulation, edema reduction, wound healing, defibrillators and pacemakers.)

If you want to see some of these quack medical devices — including the phrenology helmet and a Pulvermacher electric belt whose case is stamped with the words “Pulvermacher Galvano Co. Electricity is Life” — visit SPARK Museum in Bellingham. We also have a copy of the 1875 book “New Illustrated Self-instructor In Phrenology And Physiology,” the Fowler brothers’ famous book on phrenology. Our Whatcom County electricity museum is open 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesdays through Sundays. Visiting SPARK makes for great family friendly adventures for those looking for fun things to do in Bellingham!