It’s always surprising what visitors—especially kids—find memorable about their experience at the SPARK Museum. For some, it’s seeing the rare artifacts and original devices. For others, it’s the hair-raising demonstrations, and interactive galleries. (We defy anyone to forget seeing Elvis, the singing Tesla coil, as it blasts-out a familiar melody via 4 foot bolts of synthesized lightning. You can’t unsee that.)

Yet, of all the many artifacts, interactive devices, and demonstrations, one of the most familiar and memorable attractions—especially with younger kids–is something that doesn’t really do anything at all. It’s not an invention. It’s not necessarily priceless, but it always makes our visitors smile, especially if there are smaller children around.

We are talking about the big dog himself: Nipper, the official RCA mascot, and one of the most recognizable images in advertising history.

Way before Snoopy (1950), before Lassie (1938), before Disney’s Pluto (1930), even before the Crosley Pup (1925), there was Nipper. But unlike these other famous mongrels, Nipper was a real dog, whose name really was Nipper.

Everybody seems to recognize this iconic canine, as he stands before a vintage, wind-up disc gramophone, with his head tilted in what looks to be befuddled amazement. Universally recognized and beloved, Nipper’s delightful image helped popularize the new-and-about–to-explode sound recording industry, and brought his owner worldwide fame.

Born in Bristol, England in 1884, Nipper (Canis familiaris) is often identified as a terrier. Some say bull terrier, fox terrier, and even a Jack Russell terrier, but whatever he is, everyone agrees he’s definitely a mix-breed, which we all know really make the best dogs.

Nipper’s first owner was Mark Barraud (1848-1887), a struggling theatrical scenic artist who worked at the old Prince’s Theatre on Park Row, Bristol. Nipper was said to be devoted to his owner, and often accompanying him to work, even while changing sets during live theatrical performances. Named because of his fondness for nipping at people’s heels, Nipper also loved to chase rats and pheasants, both being abundant in late 19th century Bristol.

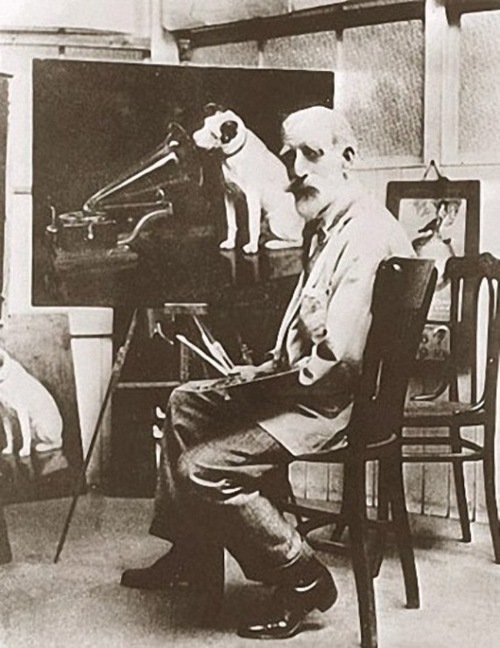

When Mark Barraud suddenly passed away in 1887, his younger brother, Francis, became Nipper’s second owner, taking him to live in Liverpool. Francis was an artist and painter, he also owned an early cylinder recording and playing machine. It was here in his new home with his new owner that Nipper first experienced recorded sound. Francis watched as his new dog became intrigued, puzzled, even mesmerized by the sounds pouring out of the horn speaker.

Talk about a memorable experience — Francis couldn’t get the image of his dog and the cylinder phonograph out of his head. Finally, three years after he passed away (September,1895), Francis decided to make Nipper the subject for a painting. Since Nipper was long dead, he used an old photo as a model for the painting, which he completed and registered on February 11, 1899 , and called it: “Dog looking at and listening to a Phonograph”. Not a particularly memorable title, to be sure, but a start.

Francis tried displaying the painting but had no success. He changed the title to “His Master’s Voice”—a definite improvement—but no takers. He tried selling the image to magazines, but still no one was biting.

Since the painting featured an Edison Bell cylinder phonograph—who just happen to be the leading manufacturer of cylinder phonographs—it only made sense for Francis to contact the Edison Bell Company and suggest they use his painting in their advertisements, which he did. Here was their response to is proposal: “Dogs don’t listen to phonographs,” (Actually, dogs do listen to phonographs, they just don’t buy them.)

Friends still liked his painting and encouraged Francis to keep trying, even suggesting changes and ways to make the image more saleable. Soon he connected with Liverpool’s newly formed Gramophone Company, who, upon seeing Nipper’s image, immediately grasped the commercial possibilities and agreed to purchase the painting and the copy write under the condition he alter the painting by removing the Edison cylinder player and replace it with their new Gramophone.

Francis Barraud gladly made the alteration, and the sale.

The newly updated painting made its first public appearance on The Gramophone Company’s advertising literature in January 1900, and later featured on some novelty promotional items. The painting and title were finally registered as a trademark in 1910. Looking back, it was a slow start with the image used only sparingly in parts of England. After years of going nowhere, the Victor Talking Machine Company–who made the Victrola record player—acquired the image and soon Nipper began to show up on both sides of the Atlantic.

Then in 1929, Victor joined the Radio Company of America and became RCA-Victor, and eventually RCA. Now Nipper would be prominently featured on record labels, record players, and radios, and soon became a familiar and beloved symbol of recorded sound—so real you and your dog will have trouble telling the difference.

The rest, as they say, is history. History we celebrate every day at the SPARK Museum. Visitors can see this heartwarming logo, and the dog that inspired it, in several locations throughout the facility. The “Radio Enters the Home Gallery” features a variety of original RCA recordings, and the authentic Victrola’s that play them. These devices are highlighted in the Museum’s color coded Visitor Guide, and demonstrated daily.

There are Nipper replicas everywhere! In the galleries, in the windows, in the display cases. Some are small enough to fit in your hand, some big enough for your kid to (carefully) put their little arms around and hug, which they do, all the time. Kids are drawn to Nipper; they just want to hug the big, friendly dog. So we let them, because we’ve learned that this can be part of a memorable experience, too.

That’s how this loyal, immensely loveable dog became one of the most famous, recognizable images in advertising history. Thanks to his creative and persistent owner, Nipper’s image is everywhere, making him the unforgettable attraction he remains to this day.

Stay grounded.