“Those who have been saved, have been saved through one man, Mr. Marconi… and his marvelous invention” – Herbert Samuel, Postmaster General

Today, whether for business or pleasure, millions of people travel billions of miles more quickly and safely than ever before. Folks are covering vast distances that were unimaginable just a few hundred years ago.

The Atlantic Ocean is a great example. Considered the busiest of the world’s great travel routes, transatlantic flights crisscrossing three thousand miles of open water, over 1,700 times every single day.

Very doable. Not a big deal. Today’s travelers have an excellent chance of arriving at their destination in one piece. It’s safe, it’s easy.

Not long ago, traveling across one of the largest oceans in the world was never safe, never easy. It’s hard to imagine how vulnerable and dangerous it was for people to travel even a short distance, just a few hundred years ago.

Traveling in 1823 meant no airplanes, no trains, no automobiles or cruise ships. No paved roads. No telephones, or telegraph wires connecting the nation. No traveling at night because there’s no artificial light, except for fire fueled by oil, coal, wood and wax.

No cell phones, no 911 to call, no Global Positioning System.

Traveling often meant not knowing where you are, or what’s on the other side of that hill. Traveling over uncharted land could be dangerous and scary. Traveling over open water was dangerous, and terrifying.

“Being in a ship is like being in jail, with the chance of being drowned.” – Samuel Johnson 1709 – 1784

Ever since Christopher Columbus stumbled upon the New World in 1492, people have been risking their lives trying to cross the Atlantic Ocean. This newly discovered continent promised the people of Europe a chance at wealth, stature, and a new life.

In 1823, Transatlantic travel was arduous, uncomfortable, extremely dangerous. Sea travel involved months in cramped, poorly ventilated quarters, nausea and seasickness, fever, dysentery, extreme heat, constipation, and the dreaded scurvy. Add to this rancid food, lack of clean water, cold, frost, dampness, and always lice.

Men, women and children faced months of uncertainty and deprivation with the ever-present threat of shipwreck, disease and piracy.

But what made it especially terrifying was the utter isolation. That feeling of no land in sight, being on open water, like the bottom could drop out from under you at any moment. Treacherous weather, rouge waves, or the always terrifying fire, could overwhelm a boat in seconds, leaving everything and everyone without a trace.

“Having someone sail away and never arrive at their destination must have been maddening for loved ones,” says John Jenkins, SPARK President and CEO. “Imagine having no way of knowing what happened, no way to call for help, the ocean just swallows you up without a trace.”

Once you lost sight of land, and something bad happens on your boat, you are doomed.

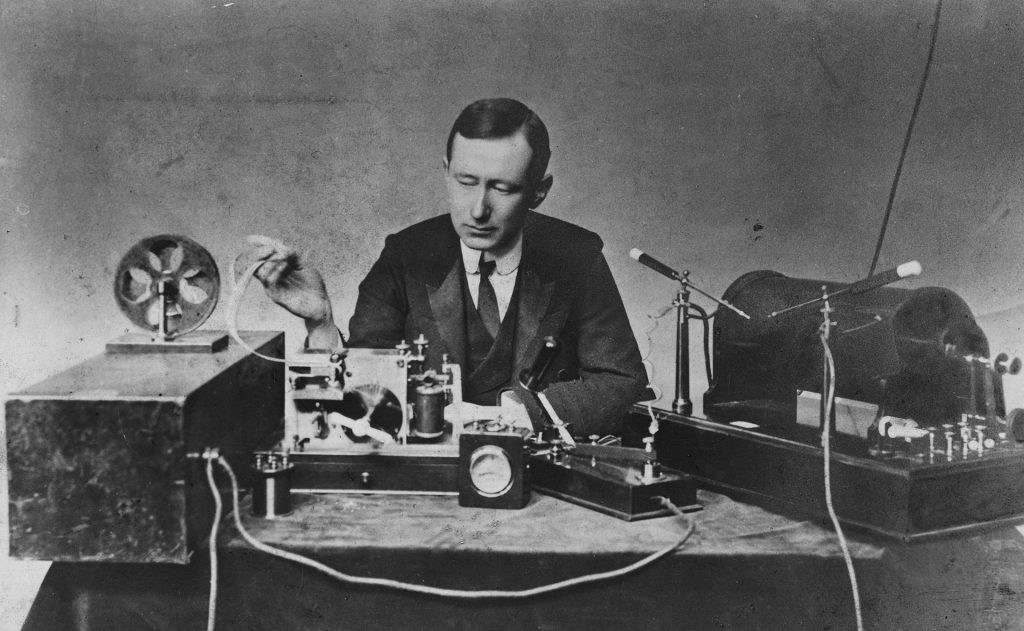

Enter Guglielmo Marconi. Born in 1874, Marconi received an excellent private education and at an early age developed a keen interest in electricity. It was Marconi who first saw the advantages and commercial possibilities of equipping ships with wireless telegraph equipment.

Building on the discoveries made by physicists like James Clerk Maxwell, Heinrich Hertz, and Oliver Lodge, Marconi constructed a device that could produce controlled modulated electric sparks, that could be translated into electric signals and picked up by a receiving device—without wires. Within a few years the name Marconi became synonymous with wireless all over the world.

In an effort to bring an end to the isolation of ships at sea, Marconi decided to create ship board wireless sets for merchant and passenger ships, and in 1900 ‘Marconi International Marine’ was formed.

After proving that wireless waves were unaffected by the curvature of the earth, Marconi successfully transmitted the first transatlantic signal over 2100 miles. By 1907 transatlantic wireless service was a huge hit, with 100s of shipboard Marconi operators snatching messages out of thin air, as they navigate an ocean of invisible radio waves.

The skill of the early operators was amazing. Sitting almost motionless, hour after hour, as they tapped out or received messages in the air. These young men were the computer geeks of their age, part of a select group of highly trained individuals, working on the leading edge of a new technology. All were exceptional, some would be heroic.

The Titanic was not the first ship to send a distress signal using Marconi wireless technology. That distinction goes to the East Goodwin lightship, which was accidentally rammed by the freighter R.F. Matthews, in a thick fog, while moored off the Dover Straights in the English Channel.

The East Goodwin had been equipped with one of Marconi’s first shipboard apparatuses, and within minutes a message had been sent to a wireless station in a lighthouse in South Foreland: “Help, we have just been run into by the steamer R.F. Matthews…Our bows are damaged.”

A lifeboat was dispatched and though the event relatively minor, it was clear that communication between ships, and between ships and the shore, was possible, practical, and necessary.

A more dramatic proof occurred some 13 years later.

On the night of April 14, 1912, the British passenger liner, RMS Titanic, the largest ship in the world at that time, struck an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City.

Titanic was fitted out with some of the finest wireless equipment available. But there was not yet an established practice of keeping a clear channel for emergency communications.

This early wireless telegraphy wasn’t like calling a person directly—instead, the channels were open to everyone at the same time. Titanic’s wireless operators were transmitting over the same frequency as other ships, and the channels were often jammed with unwanted communications. Yet that night, Harold Cottam, operator on nearby liner Carpathian, was still awake.

Cottam received the first distress signal from Titanic, sent by senior wireless operator John “Jack” Phillips. The Carpathian immediately turned and steamed the almost 60 miles towards Titanic’s given position, a trip that would take almost four hours.

For two hours Phillips and assistant operator Harold Bride continued to tap- out a stream of distress signals (the Marconi Company distress signal was “CQD”) and messages that were picked up by other vessels. At some point Bride asked Phillips to switch from CQD to the new international distress signal: “SOS” which he did.

At approximately 1:45am, Cottam received Titanic’s final Morse code message: “Come as quickly as possible, old man, the engine room is filling up to the boilers.” Cottam replied that “All our boats were ready and we were coming as hard as we could come.”

He received no further response.

Of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died, making it the deadliest sinking of a single ship up to that time.

And four days later, Carpathian steamed into New York harbor carrying 706 survivors. Without wireless, it’s safe to say there would have been no survivors at all. Like so many ships before it, Titanic would have sunk to the bottom of the ocean, and no one would ever know what happened. Just vanished.

It’s hard to imagine a more dramatic demonstration of the power of wireless communication. Only months after Titanic was lost, the Radio Act of 1912 was passed, allowing the US government to gain control of the airwaves, and required all wireless operators to hold a valid federal license to use radio equipment.

Soon all first-class passenger ships had a permanent 24-hour radio watch, and required to maintain radio silence at regular intervals to listen for distress calls.

Marconi became an international celebrity. Rescuing over 700 passengers from Titanic using his wireless communication system conferred heroic status on him and his invention, even if he did go on to become best man in Mussolini’s wedding.

Stay grounded.