When we think of our favorite Christmas traditions, 19th century London always come to mind. The Brits do a great job with the holidays, being the home of Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim, roving Carolers in Victorian outfits, the Queen’s speech, mulled wine, and of course, Old Father Christmas.

Yet, of all these venerable Christmas traditions, few are more popular than the Royal Institute’s annual Christmas Lectures, a series soon to celebrate 200 years of science created especially for young adults.

Today, for millions of free-thinking, science enthusiasts it just isn’t a proper Christmas holiday without this annual BBC broadcast event.

The Royal Institute was founded in 1799, in the house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph Banks (1743-1820). Banks was the eminent English explorer (sailing with Captain Cooke) and is noted for his appreciation and promotion of the natural sciences. He and his fellow natural philosophers established the Royal Institute in an effort to support their Nation’s agriculture, industry and overall future through experiment-driven discoveries testing the natural world. They wanted the Institute to feature working laboratories, display areas, libraries, meeting rooms and a theatre for lectures and grand demonstrations.

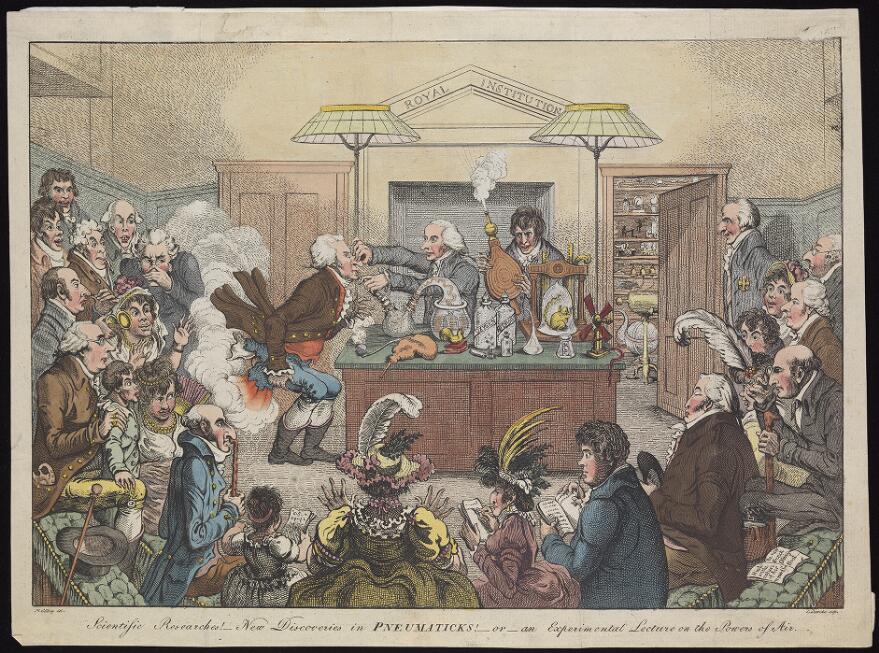

Completed in 1802, the Theatre seated as many as a thousand visitors. The audience sat stacked around a semicircular stage & demonstration table, often covered with strange looking devices and contraptions, poised to astound and delight.

Banks and his fellow natural philosophers (still a very closed and exclusive club) wanted to share their discoveries through dynamic lectures and spectacular demonstrations. They wanted to make an impact on their fellow countrymen. They didn’t have to wait long.

It was Humphry Davy (1778-1829) who first established the Royal Institute as a place for fantastic and engaging lectures, as well as a place for scientific research. Davy was a Professor of Chemistry whose afternoon lectures were so popular with the public they caused (carriage) traffic jams up and down Albemarle Street, a major thoroughfare in central London, ultimately creating, out of necessity, the City’s first one-way street.

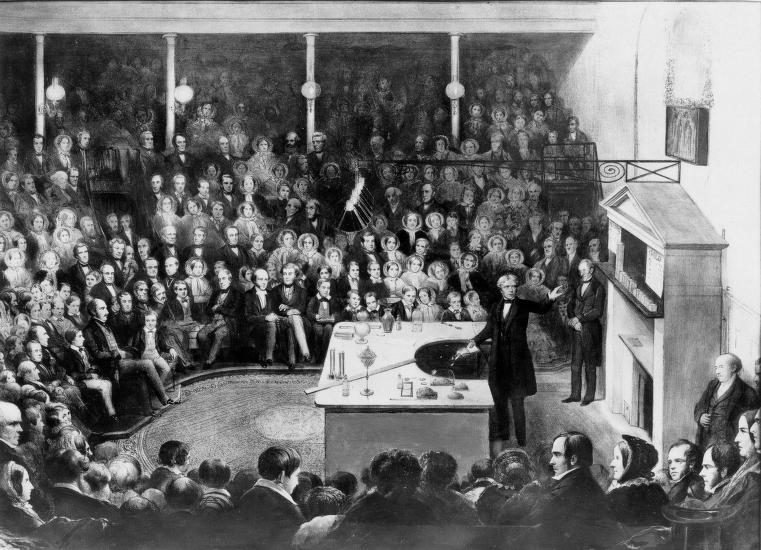

Yet it was Davy’s assistant, the brilliant Michael Faraday (1791-1867), who established himself as London’s most popular and beloved scientific lecturer. Faraday was the son of a blacksmith and had little formal education. It was as Davy’s devoted assistant that Faraday’s excellent skills as an experimentalist began to develop, ultimately surpassing Davy, and becoming one of the most influential scientists in history.

Faraday’s major contributions include discoveries in electrochemistry, and electromagnetic induction, providing the basis of the electric motor.

He was said to have a wonderfully clear and engaging manner, making his lectures and presentations wildly popular with everyone, especially the general public, who appreciated Faraday’s confident, methodical delivery.

Always looking for ways to engage younger people in science, and building on his other popular series, Friday Evening Discourses, Faraday created the first Christmas Lectures, a series of presentations for younger audiences, to be given throughout the holiday.

“The course of lectures should be delivered at the Royal Institution, at the Christmas, and other vacations, on some of the leading branches of Natural Philosophy, adapted to the juvenile audience.” – The Times 17 December 1825

Interestingly enough, the first Christmas presenter was not Faraday, but the English engineer, John Millington (1779–1868). Millington served as professor of mechanics at the Royal Institution from 1817 to 1829 and on December 17, 1825 he delivered the inaugural Royal Institution Christmas Lecture. It was the beginning of a series featuring many outstanding presenters from a variety of scientific disciplines, including several Nobel laureates. Chemistry, biology and engineering have been the most repeated topics presented, but the list also includes astronomy, physics, math and music. Only two Americans—Philip Morrison 1968, and Carl Sagan 1977—were invited to hold court in what still remains a very British organization.

“For the last 8 seasons, professor Faraday, has undertaken this task with a modesty and a power which it is impossible to praise too much. There can be no greater treat to anyone fond of scientific pursuits than to attend a course of these lectures.” – Illustrated London News, 1861 Pg 29

Faraday was to host a record 19 Christmas Lecture series before retiring. His most famous topic and lecture series, 1848’s “The Chemical History of a Candle”, involved the chemistry and physics of a candle flame—something everyone—even young people—were familiar with. It was Faraday’s genius, taking the simplest household object, a candle, and phenomena, a flame, and using it to illuminate so many aspects of the natural world.

His demonstrations were mind-expanding and amazingly diverse, including the production and examination of various gases, the properties of water and relative volume of steam, and techniques in measuring atmospheric pressure, all from the properties of a common household item.

Faraday emphasized that several of his demonstrations and experiments performed in the Lectures could and should be duplicated by children at home, including proper attention to safety. The Lectures were first printed as a book in 1861 and became one of the most successful science books ever published.

The Christmas Lectures went from the pulpit to the world when, in 1966, the BBC began their annual televised broadcast. Now everyone can enjoy a shot of holiday enlightenment via the telly, the internet, even on your cell phone—reminding everyone how exciting, accessible and empowering science can be.