“I am attacked by two very opposite sects: The scientists and the know-nothings. Both laugh at me, calling me the frog’s dancing master. But I know that I have discovered one of the greatest forces in nature.” -Luigi Galvani – 1791

It’s always worth remembering that many of nature’s greatest secrets were unlocked by people just like you and me; people taking a moment or two and questioning something right before them. Whether it’s a drop of rain on a window, or a static charge leaping from a door knob to your hand, it’s always interesting when looking at the object or phenomena as if seeing it for the first time. That spark can be mesmerizing—even mind-blowing—if studied with fresh eyes and an open, curious mind.

Here are a few brief, yet historic examples of people making profound discoveries by putting Mother Nature to the test:

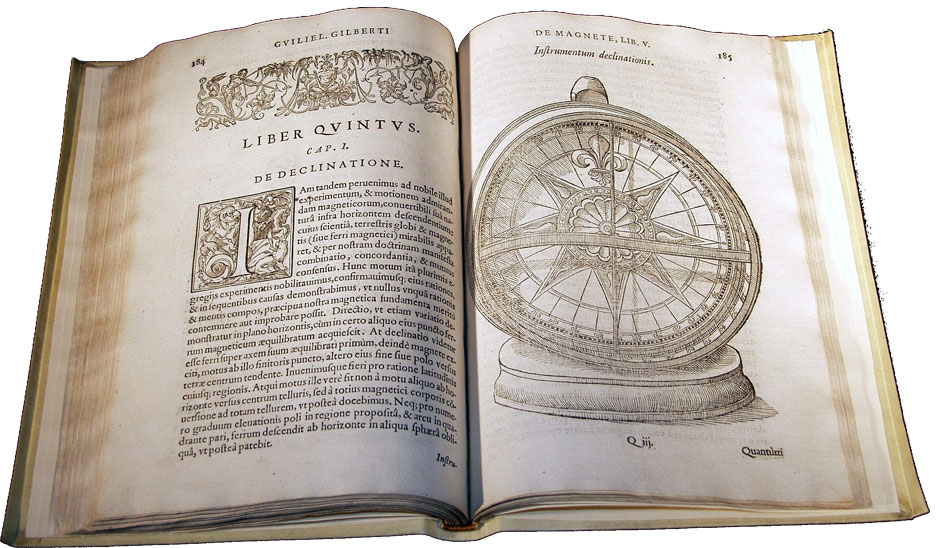

- William Gilbert publishes ‘De Magnete’ in 1600 and discovers that the biggest magnet on earth, is the earth!

- Isaac Newton completes ‘Mathmatical Principles of Natural Philosophy’ in 1687, and proves that the same force making an apple fall from a tree also causes the moon to orbit the earth!

- Benjamin Franklin writes ‘Experiments and Observations with Electricity’ (1751), where he discovers that the spark on his friction machine is exactly like a bolt of lightning in the sky!

- Luigi Galvani published his essay ‘Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion’ (1791) and reanimates dead tissue, discovering “animal electricity”, the vital spark of life!

Or so at first it seemed.

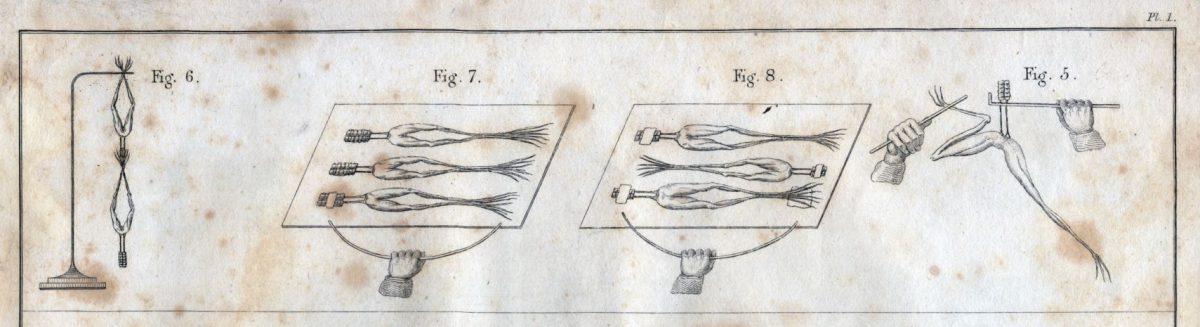

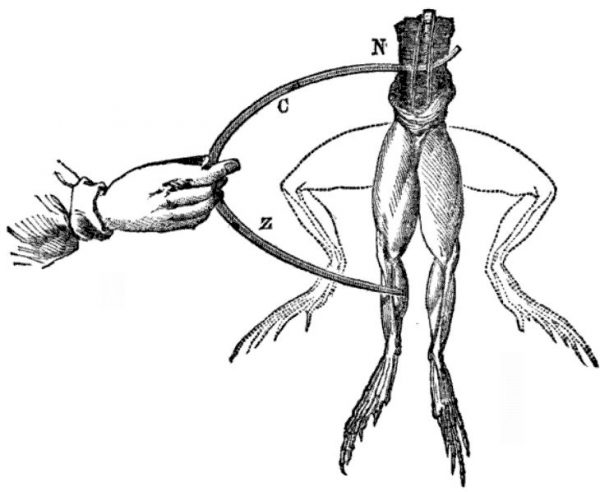

In 1791, Italian physician Luigi Galvani was applying scientific method to his experiments with static electricity and its effects on muscle contraction, and his findings were truly shocking. When touching the nerve or muscle of a recently deceased frog with a metal scalpel, the legally dead amphibian leg jolted and contracted violently as if alive, leading Galvani to the theory of a unique ‘animal electricity’.

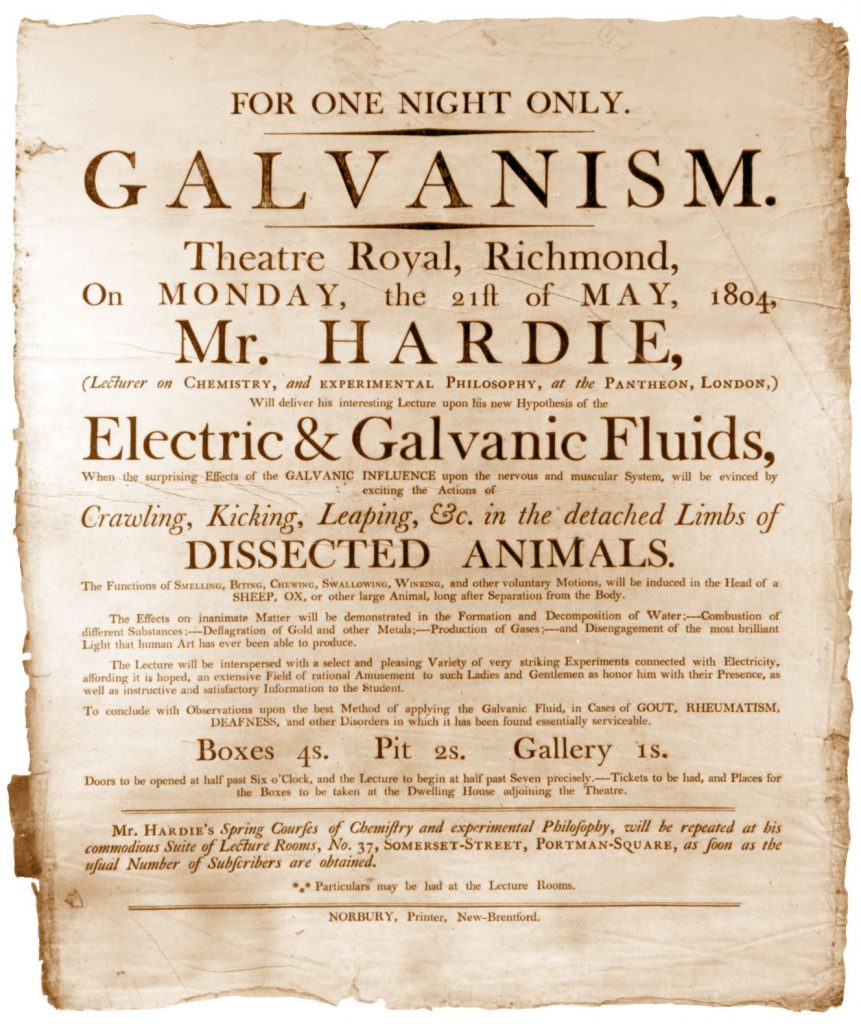

Soon fellow natural philosophers all over Europe and the colonies were recreating Galvani’s gruesome experiments, as they attempted to manipulate the spark of life.

At first Galvani’s findings were met with cautious optimism by the international community of scientists, including fellow countryman, Alessandro Volta, a professor of physics and early supporter of animal electricity. But after carefully studying Galvani’s experiments, Volta revised his opinion, finding that something completely different was happening. Upon further investigation, Volta discovered that Galvani wasn’t igniting innate animal electricity, but inducing an electric current flowing between two dissimilar metals, like iron and brass. The newly executed frog was acting as a conductor, and the electric current was stimulated the still living cells in the animal’s nerves and muscle tissue.

Volta decided to dispense with the frog all together, and built a stack of alternating zinc and silver discs separated by cardboard soaked in salt water and demonstrated that an electric current flowed when the ends of the tower were connected.

Volta didn’t discover animal electricity, but he did invent arguably the greatest electrical invention of all time: the battery.

“Volta’s Pile was the first battery capable of producing a continuous electric current. Virtually every electric invention of the 19th century (and there were many!) was directly dependent on it, which is why I call it the most important invention in the history of electricity.” –The Untold Story of the Telegraph, John D. Jenkins

You’d think it would end there, but it didn’t. Actually, it got a lot worse.

Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, took animal electricity demonstrations to a whole new level. It was Aldini’s outrageous public demonstrations that inspired Mary Shelley. How could they not, when reading and hearing—if not seeing—public demonstrations where a strong electric charge is shot through a recently deceased body—sometimes fresh from the gallows, only to see the corpse bolt upright on a table, with legs and arms flailing as the torso convulses and shocks an audience of astonished onlookers.

“It was on a dreary night in November, that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning, the rain pattered dismally against the panes and my candle was nearly burnt-out when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull, yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.” – ‘Frankenstein’, or ‘The Modern Prometheus’ by Mary Shelley 1818

We admit, Aldini put on a heck of a show, but reanimating matter he and his Uncle were not. The simple fact is the cells in our bodies do not die when we breathe our last breath. The body shuts off in stages as muscles and nerve cells continue on their own. (That’s why blood transfusions and organ transplants are possible.) We know that applying an electric charge to muscles or nerves will make those cells contract. This remains true for the newly deceased, as well. All Aldini did was give an unforgettable demonstration of muscle and nerve connectivity—and inspire the greatest mad-scientist-gets-unintended-consequences novels of all time.